The RAF

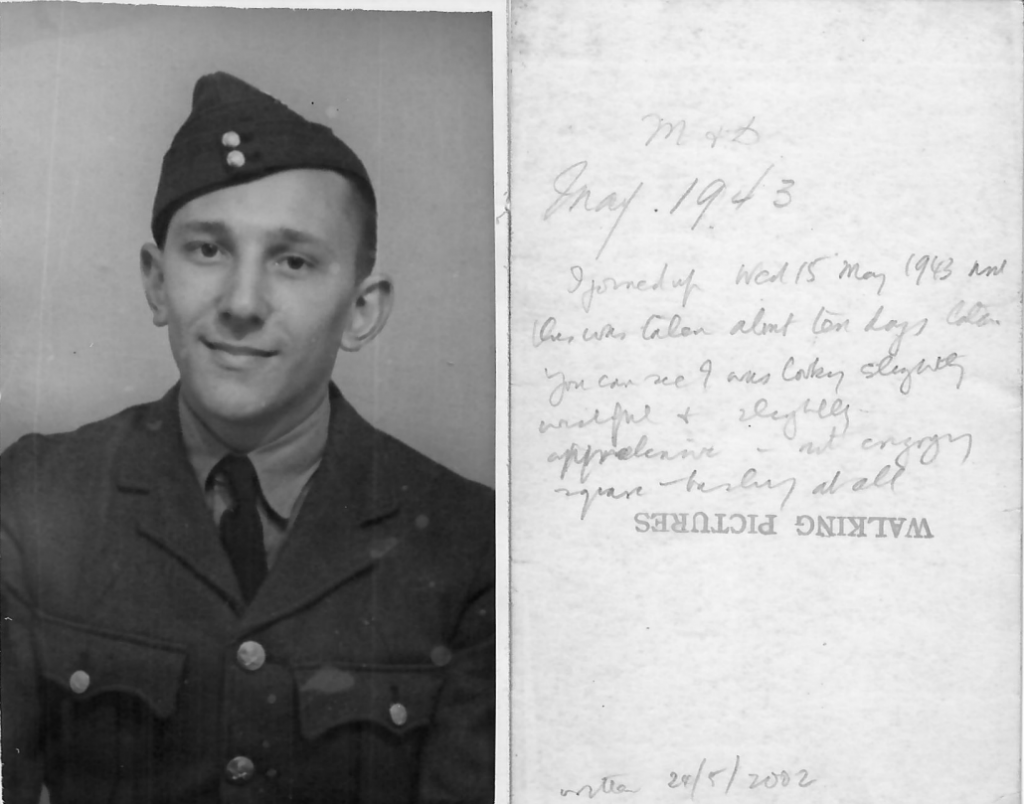

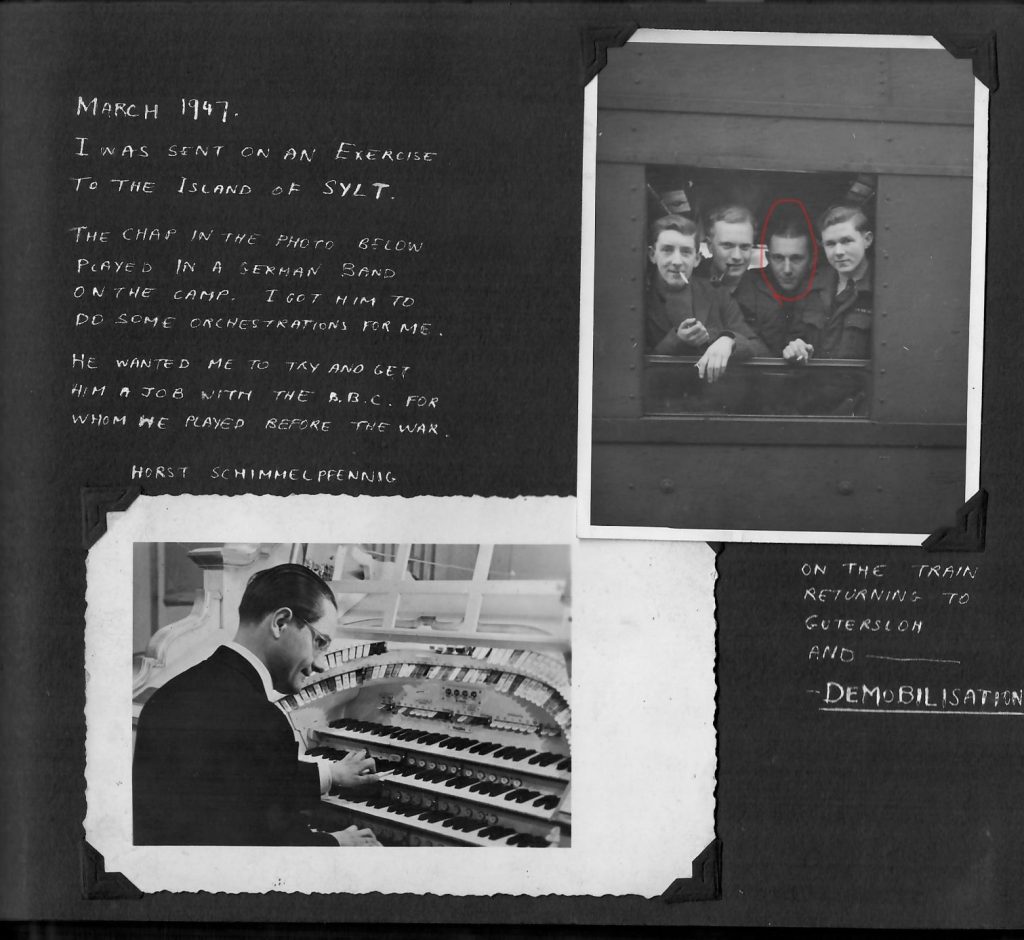

Don served in the RAF from 25th April 1943 to 6th May 1947.

After his 6 weeks basic training at Cardington, he was sent to No 7 Radio School South Kensington to be trained as a Radar Mechanic. In March 1944 he was transferred to Servicing Echelon Lasham Hampshire where he seemed to move around between various squadrons, but mainly with 107 Squadron and 305 Squadron (A Polish Squadron). He was sent to Epinoy France with 305 squadron in November 1944. In August he was posted to 6021Servicing Echelon, Melsbroek, Belgium. He remained with Squadron 21 until his release from the service, including 2years as part of B.A.F.O. (British Air Forces of Occupation in Germany) based at Gutersloh.

Editors Note – Information on the structure of the RAF and the Squadrons Don was attached to can be found below.

The first mention in the Diaries of being called up is on 6th January 1943 when he just noted that he has to register on Saturday, and on the Saturday he simply stated the time he registered and that he had ‘put down for flying duties.’

Saturday 12th February 1943 he had his medical.

He spent 3 days at No 2 Recruits Centre, Cardington from 20th April 1943. He puts in a large amount of detail about this 3 day assessment. He did not like the process, or the food, and was disappointed to be turned down for Air Crew but was allocated to RDF Radio Direction Finding later know as Radar. On the last date he noted his number is 1876276 A.C.H. Redhead.

His RAF Record of Service (ROS) details that on 26th April 1943 he was enlisted to The Reserve and sent home until called forward for training. (Editors note more information can be found on the RAF Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR) under the section on the RAF structure below)

Between the assessment and being called up, he made the most of playing in his dance band and spent a lot of time with friends and family going to the cinema and shows. Although he wrote very little in the diary’s about how he was feeling, he did note he felt “rotten” when he had to say goodbye to everyone at work on his last day. I was also interested to learn that often even complete strangers would slip money into his pocket when they heard he was “going up” into the forces. Link to 15th May 1943

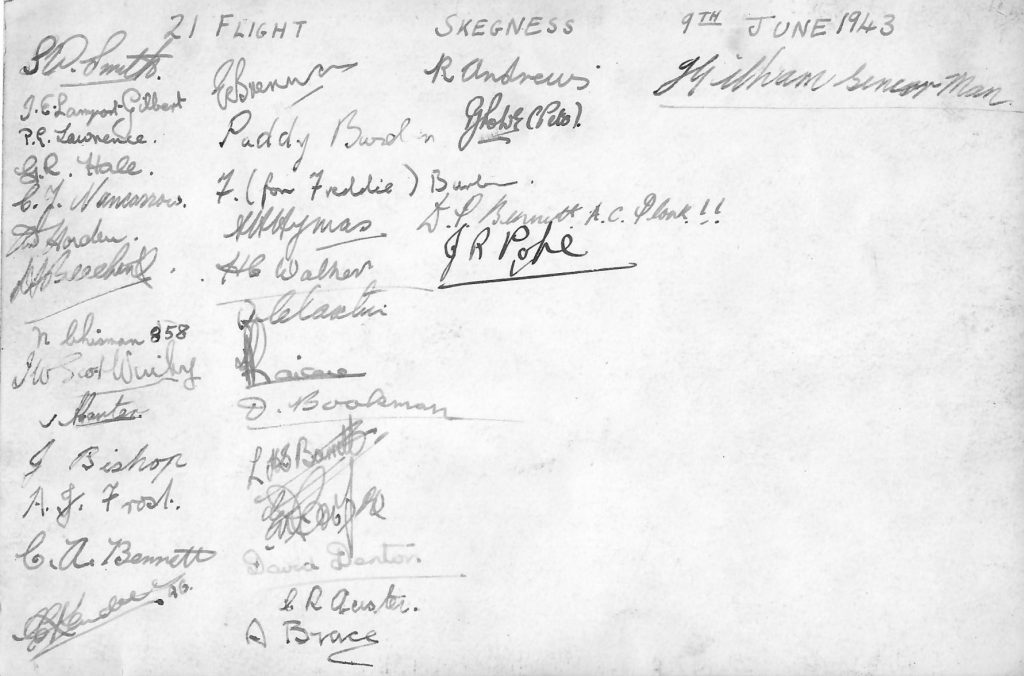

The information in his diary was very muted for the day he left home on 18th May 1943. His formal Record of Service (ROS) notes he was posted from the Reserve back to No 2 Recruits Centre, and then 2 days later he was posted to No 2 Recruits Centre, Skegness for his 6 weeks basic training.

From this time, his letters home contained lots more interesting information. Letters were obviously extremely important to him and his family, and there was much consternation when the post was delayed. It is also evident that between them they are trying to play down any dangers and privations each are suffering to try to stop too much worrying. The letters make it very clear that the doodle bug bombs were particularly nasty. Many parcels are sent between Don and the family including sending food, newspapers, music, and much else besides and his mother often still did his washing!

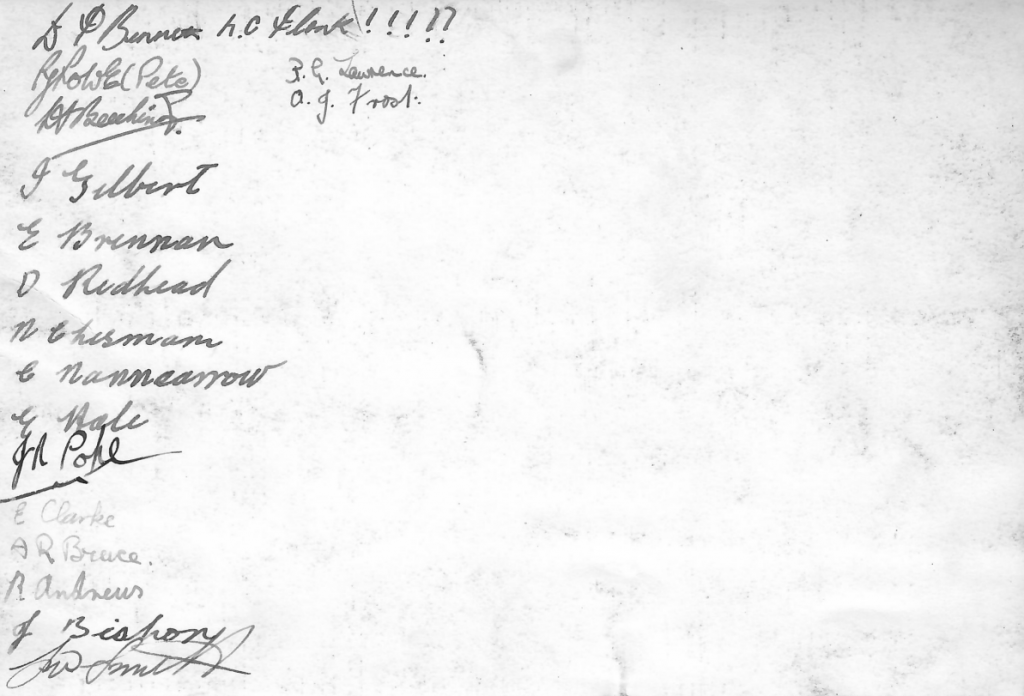

During his first 6 weeks in the RAF he clearly did not like square bashing, unnecessary rules and awkward officers, but he was pleased how fit he became and detailed many good times with the guys he was billeted with. Lots of inoculations are mentioned both in the letters and diaries. He also almost immediately started night school.

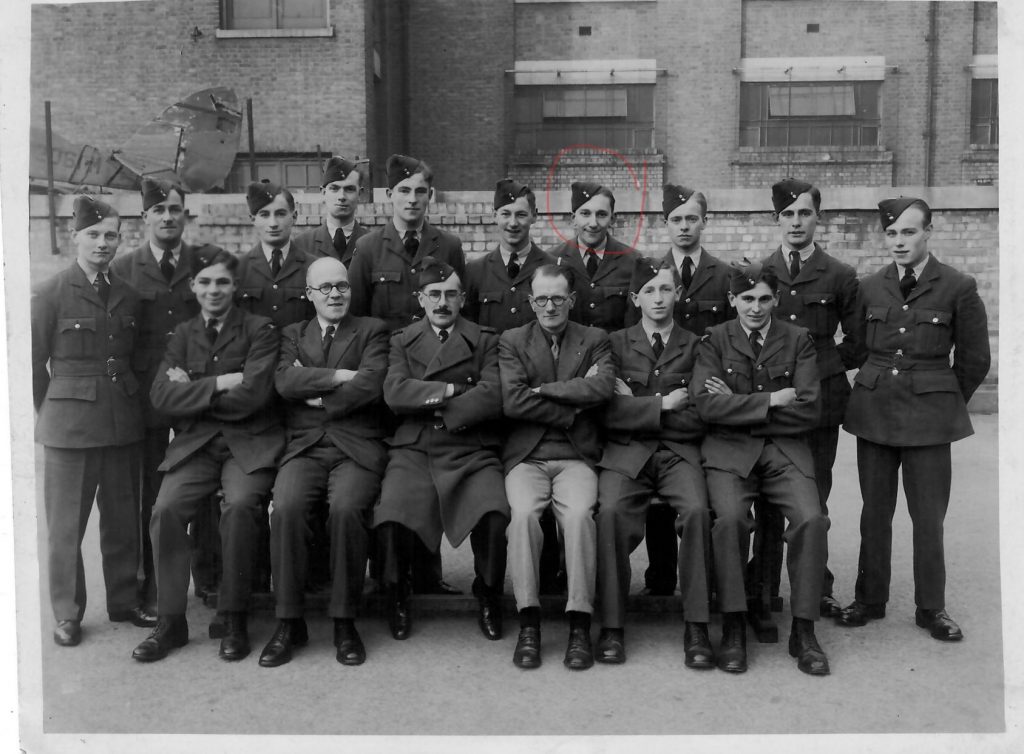

His ROS records that on 1st July 1943 he was allocated to No 7 Radio School South Kensington, London. However the Diary details that Don was delighted to be sent to London Northern Polytechnic, Holloway Road, Islington Class 12C for his electrical training.

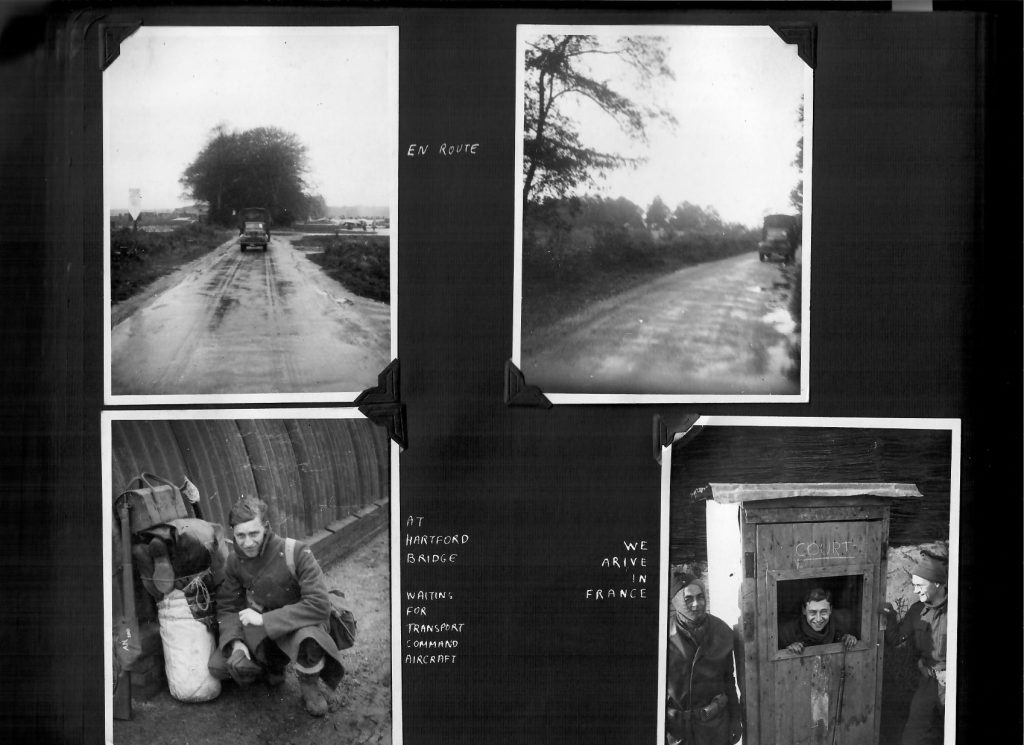

The ROS whilst normally very detailed just records South Ken, but his diary notes that he moved there in December that year. He had very comfortable lodgings in Islington and was able to go home almost every weekend and some evenings and was therefore able to continue playing in his dance band. The course ended in December that year and he passed “about 5th” in the class. Half of them were sent to Bolton and he was again delighted that he was sent to South Kensington for further technical training, arriving on Wednesday 22nd December. Don was very pleased that he was in the military band on Alto Sax and he was home from Christmas Eve until Monday 27th December. He passed out as AC2 on Wednesday 1st March 1944 and was posted to Hartford Bridge Hampshire.

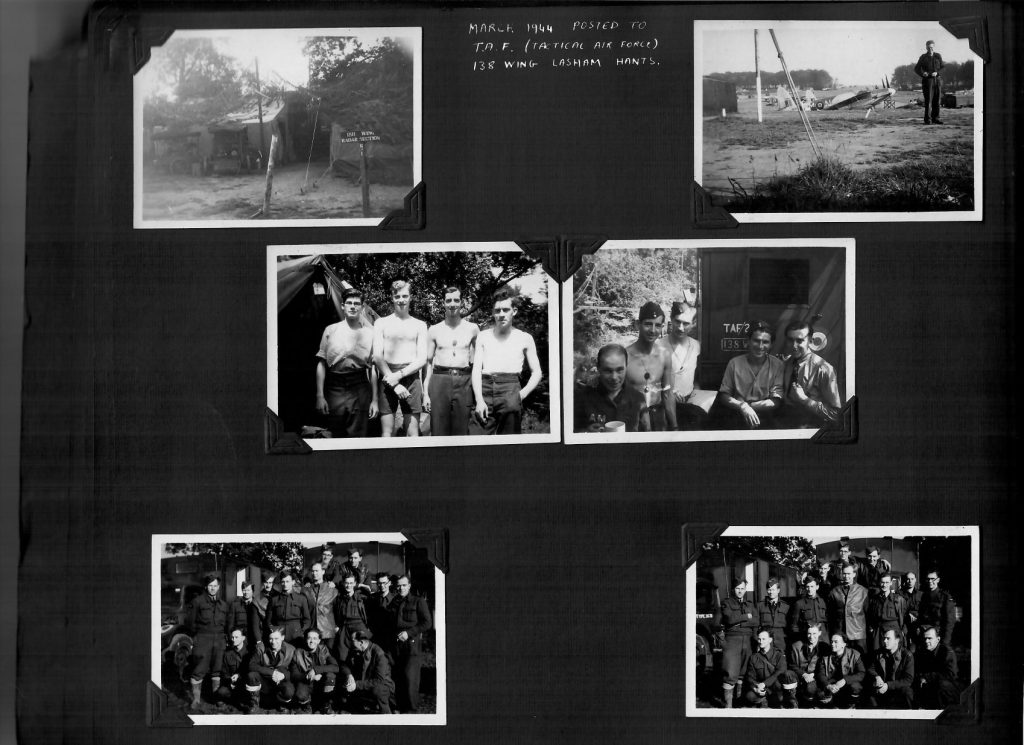

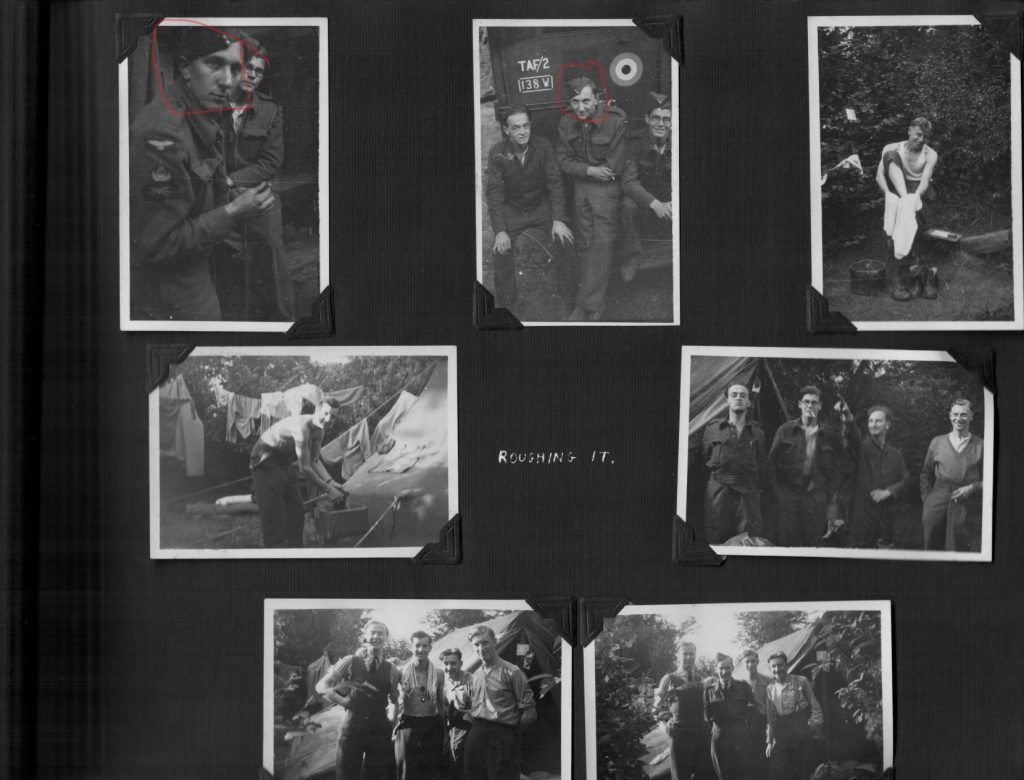

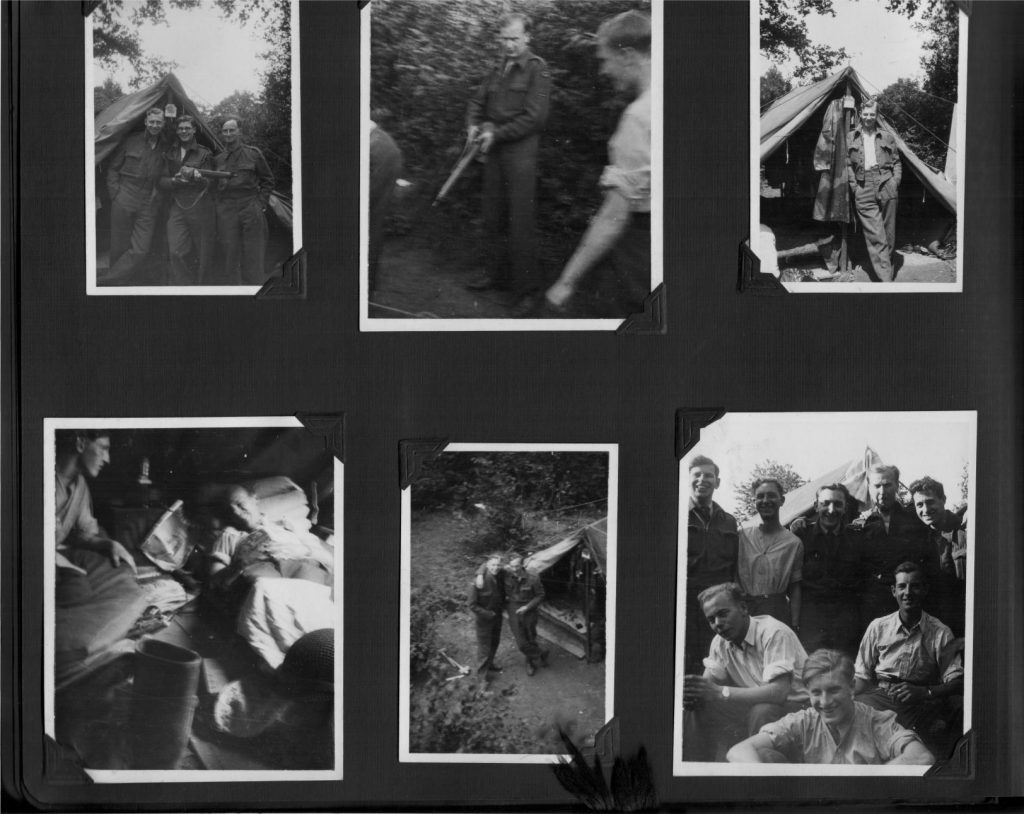

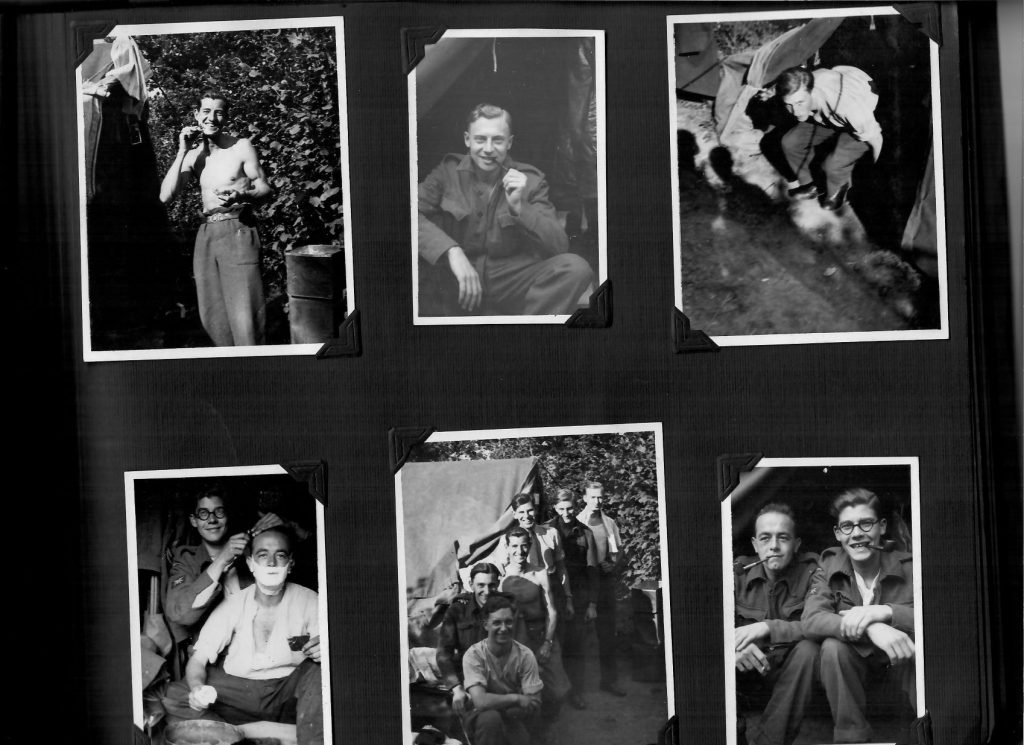

However, when he was due to leave he got dysentery and was in St Marys hospital for 8 days. He was allowed home for 1 night and then had to make his way to Hartford Bridge but when he arrived he found 3122SE had moved to Lasham. Don finally arrived on Saturday 18th March. The RAF records his hospital stay and that his unit was No 3122 Servicing Echelon, Lasham Hampshire from 8.3.44. He discovered he was in TAF2 and “it looks like we are in 2nd front”. (Editor’s note further information on the RAF structure below) Almost immediately he was put into the advance party for going under canvas. It did seem a little disorganised as he wrote that some days they seemed to put down more tents than they put up. He was also very angry about how the officers were being treated much better than the men. Link to 28th March 1944

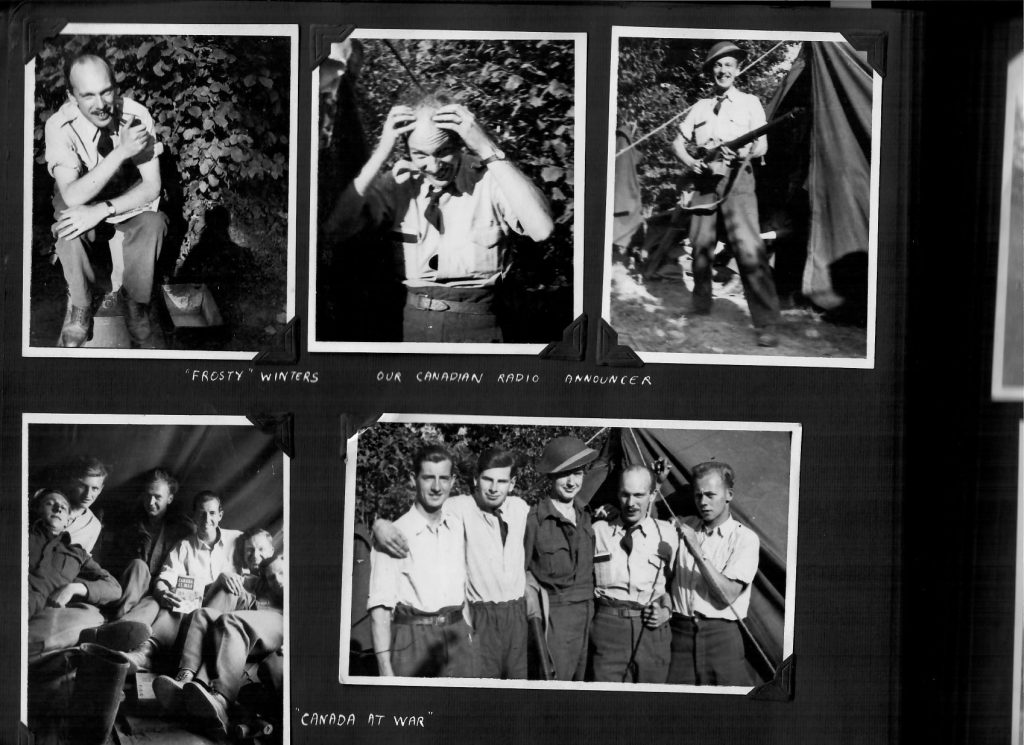

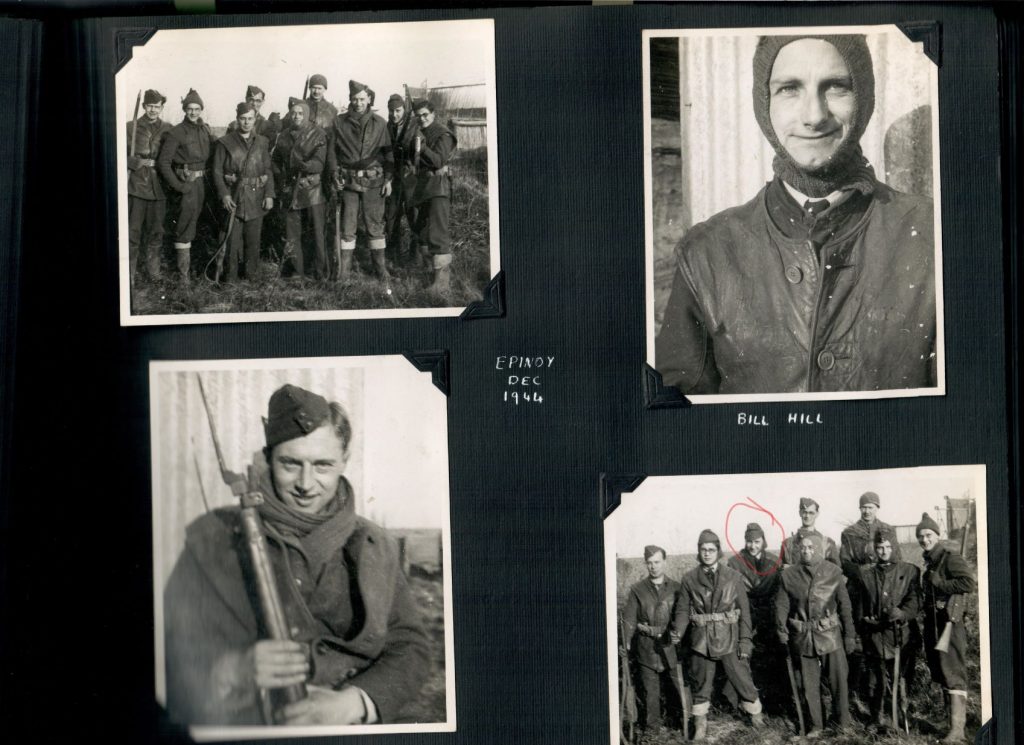

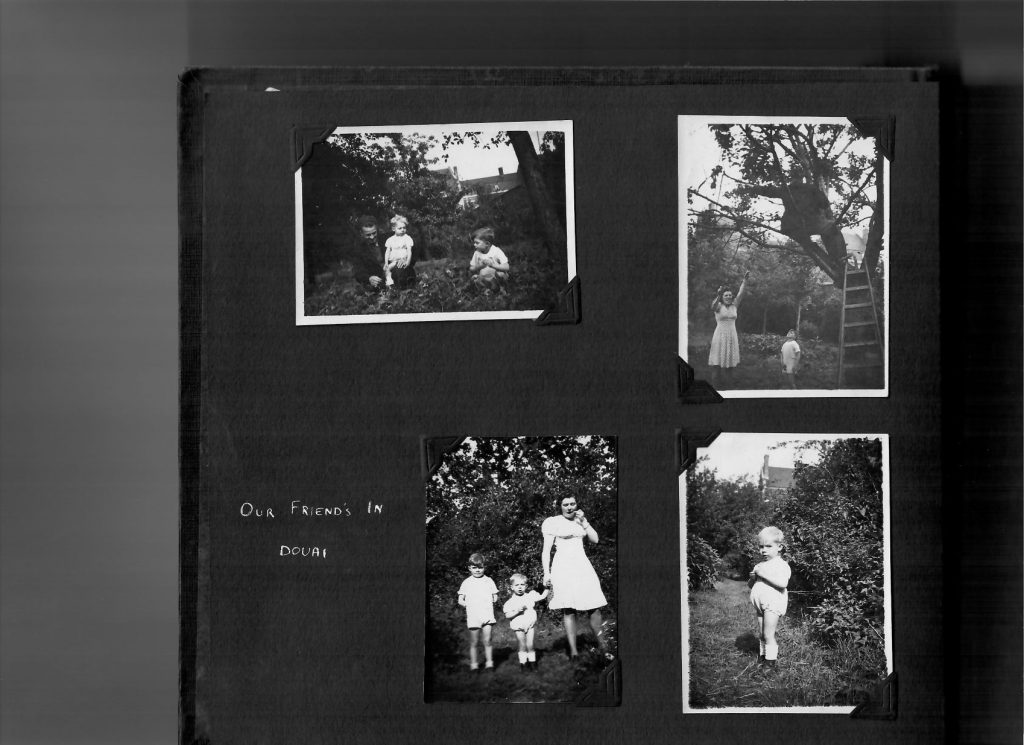

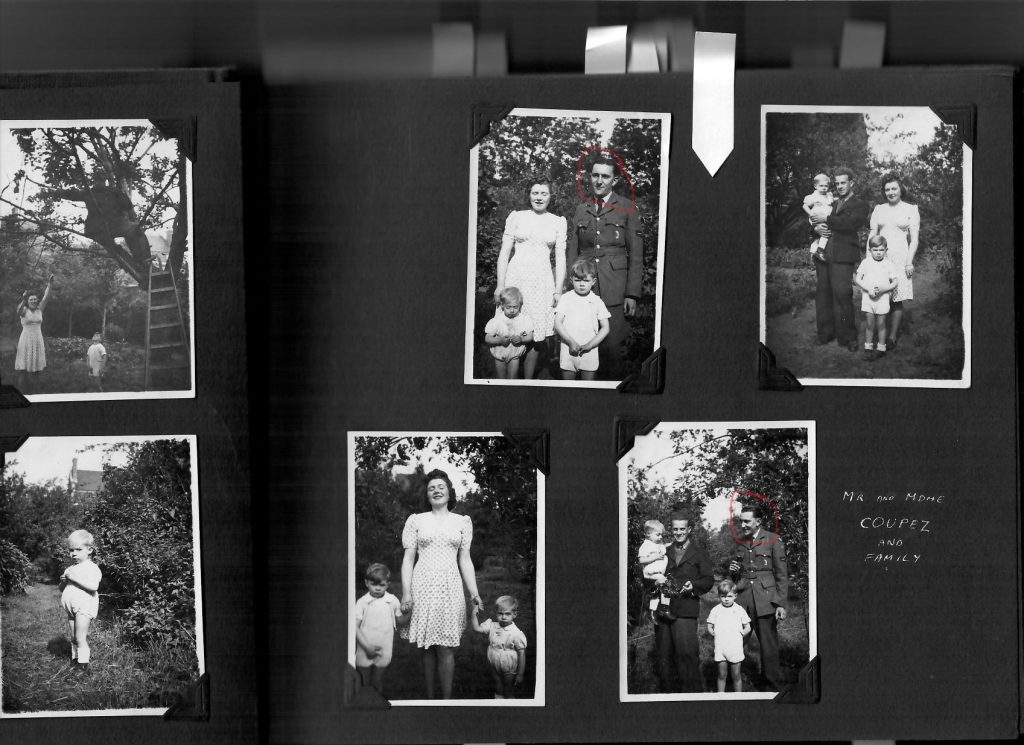

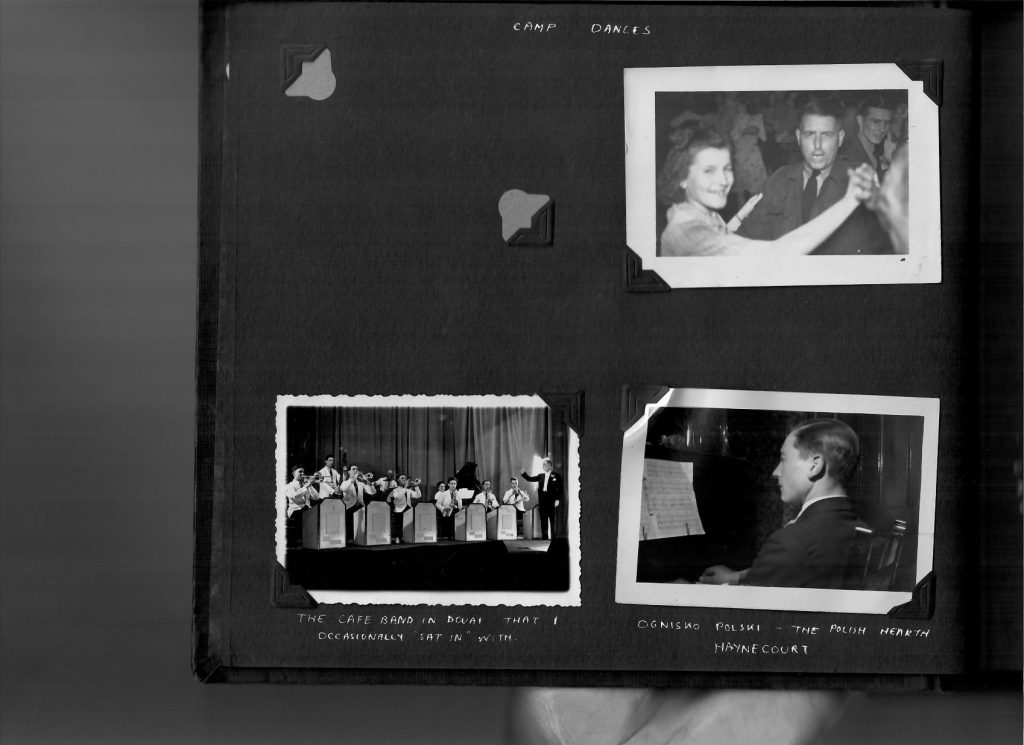

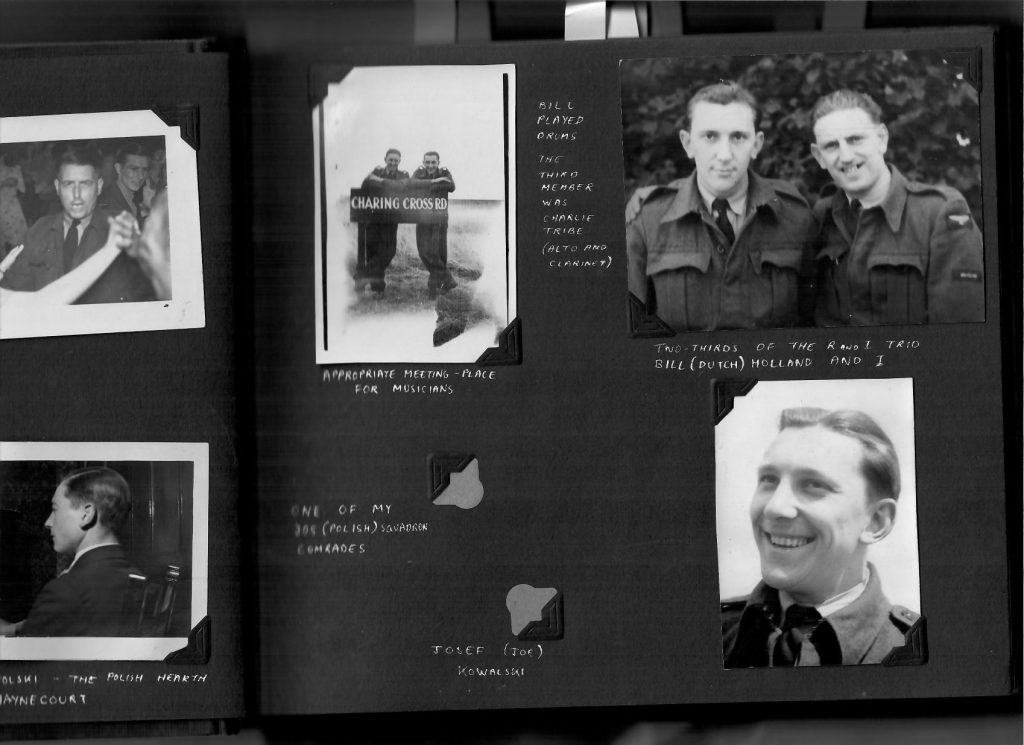

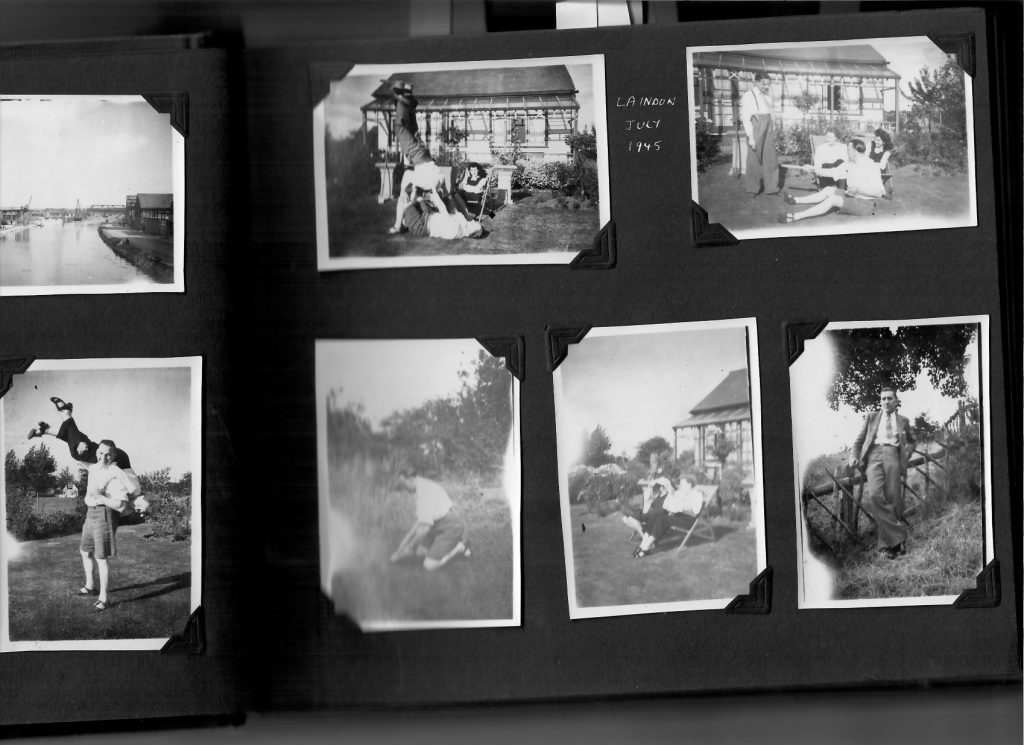

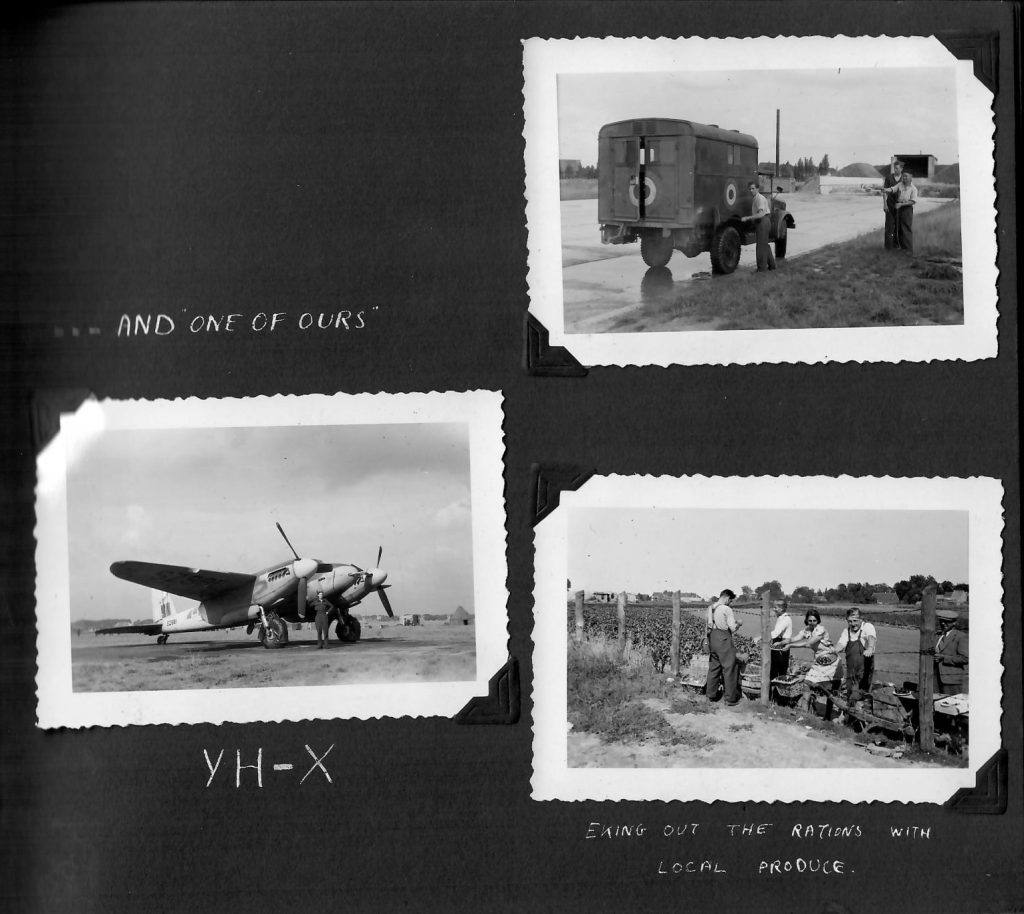

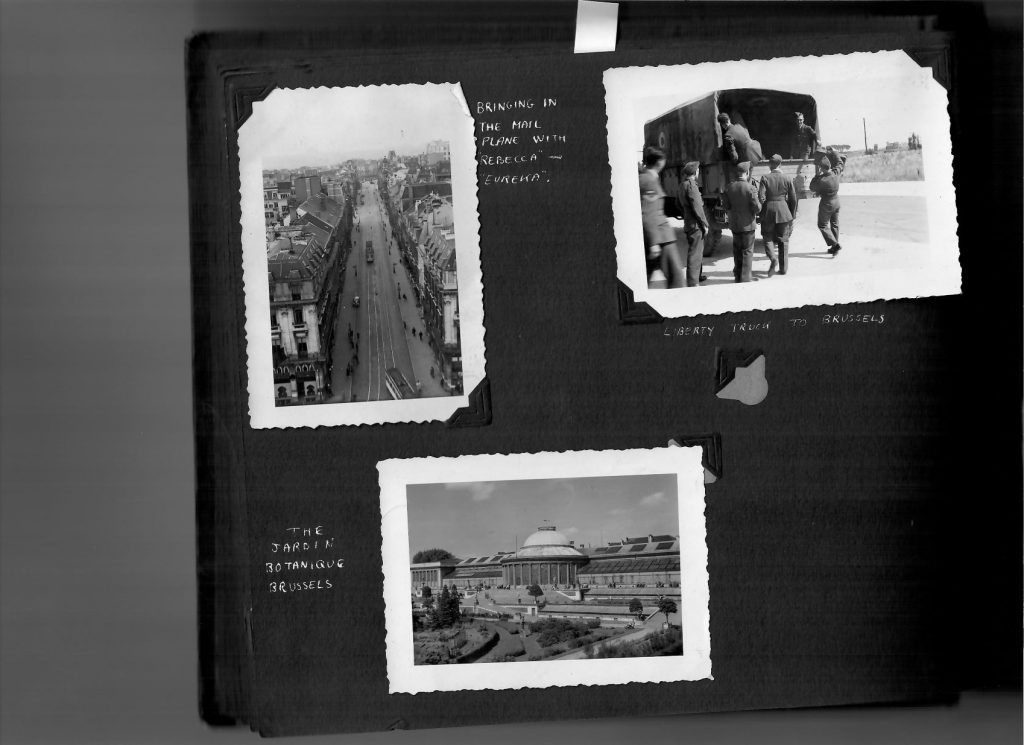

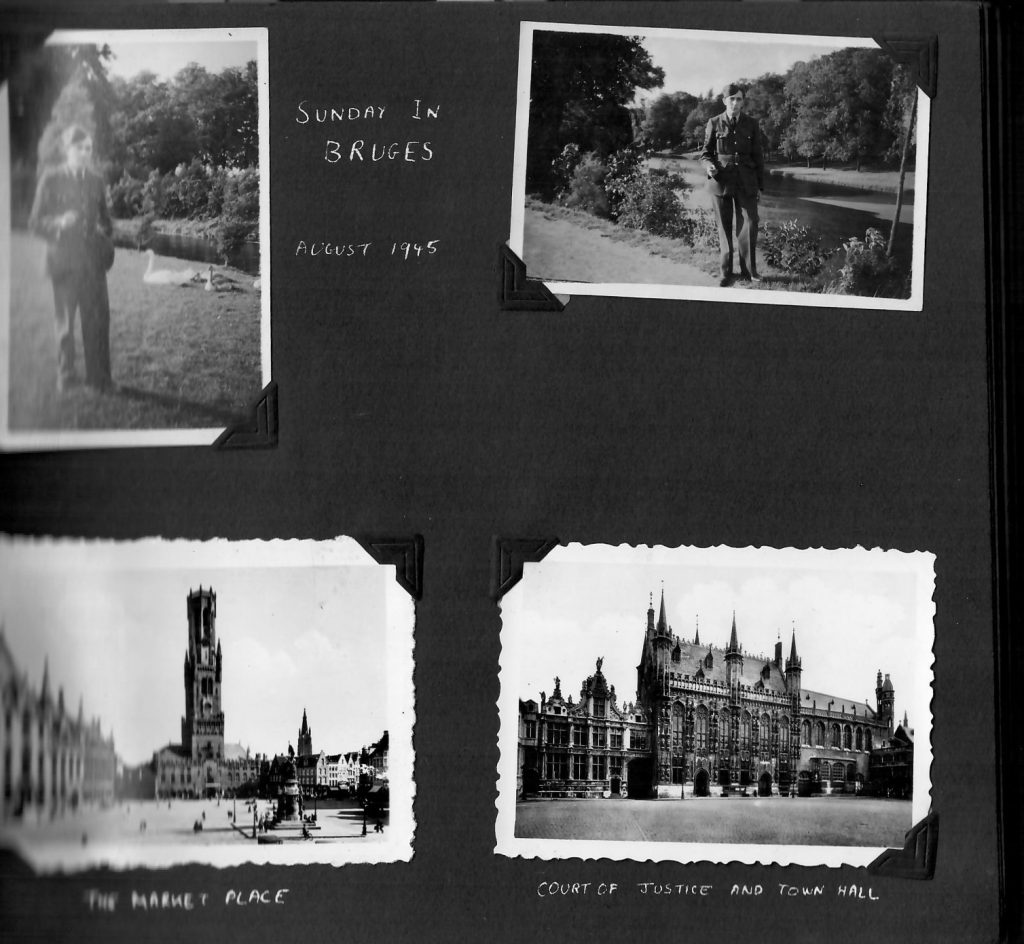

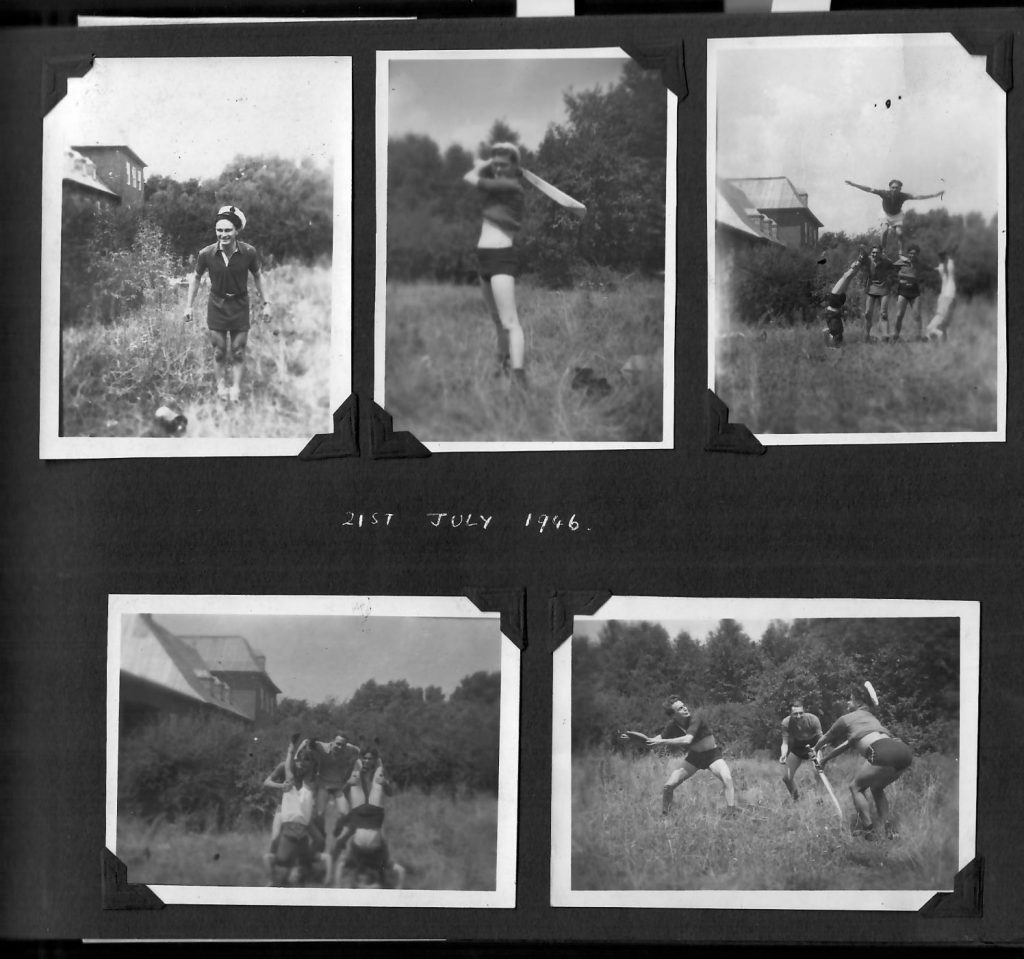

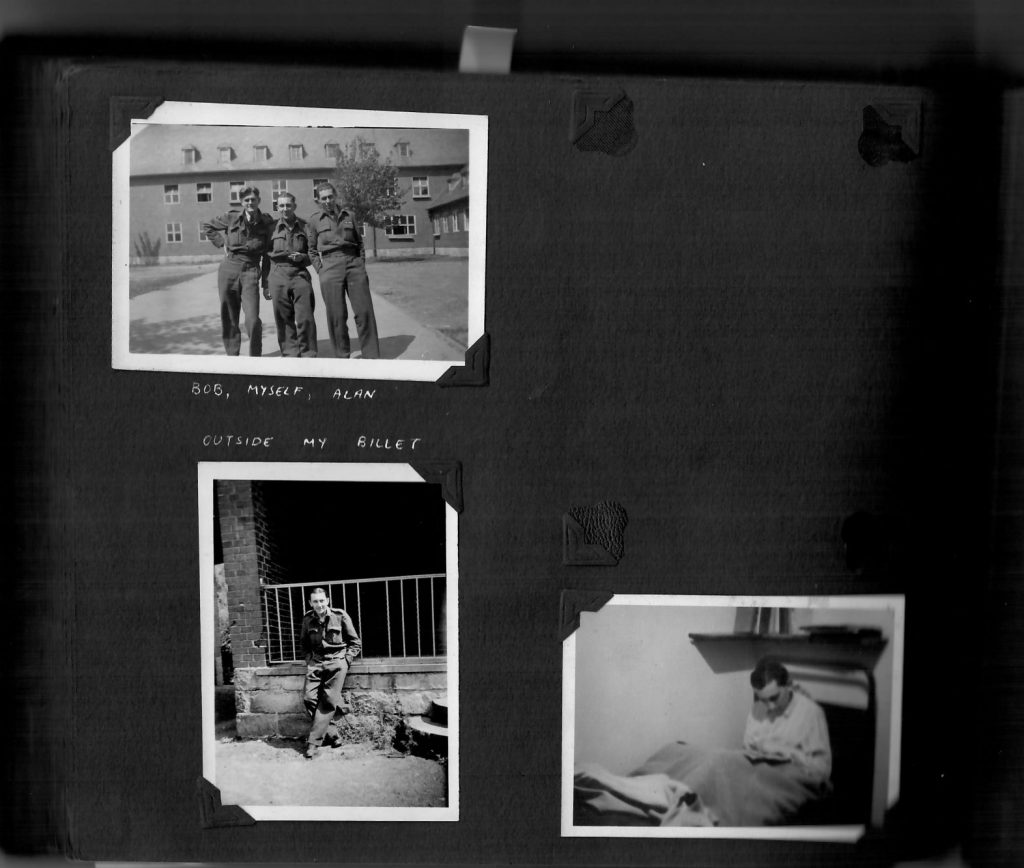

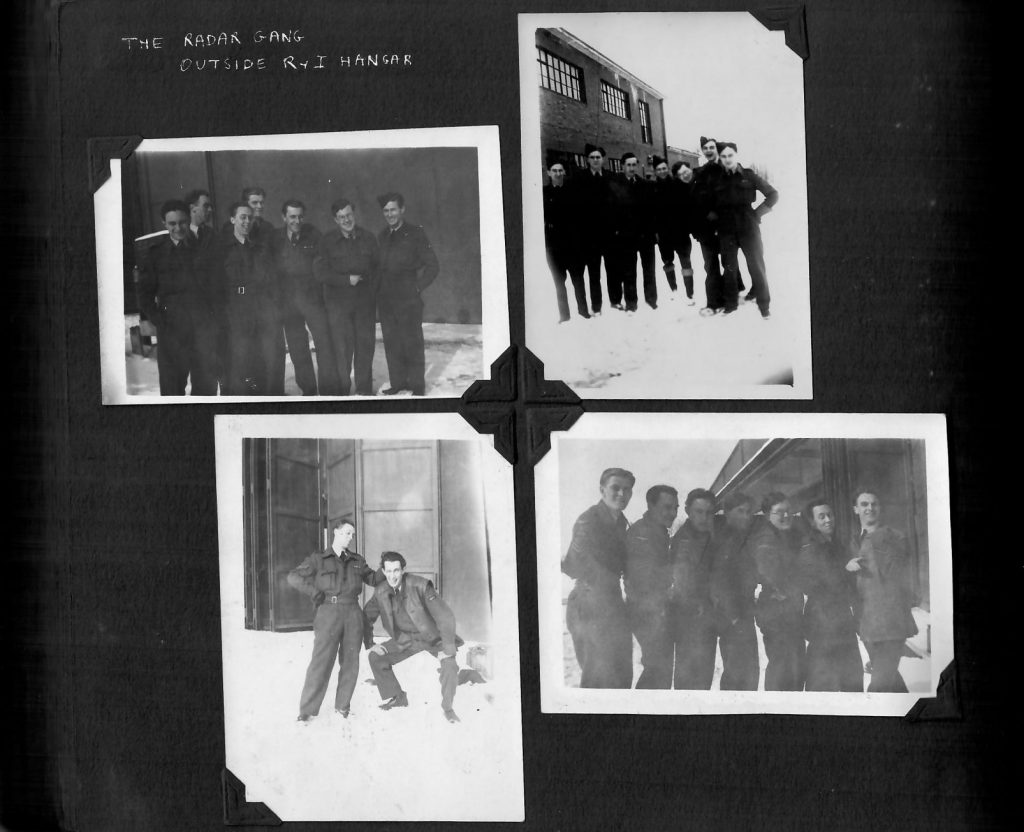

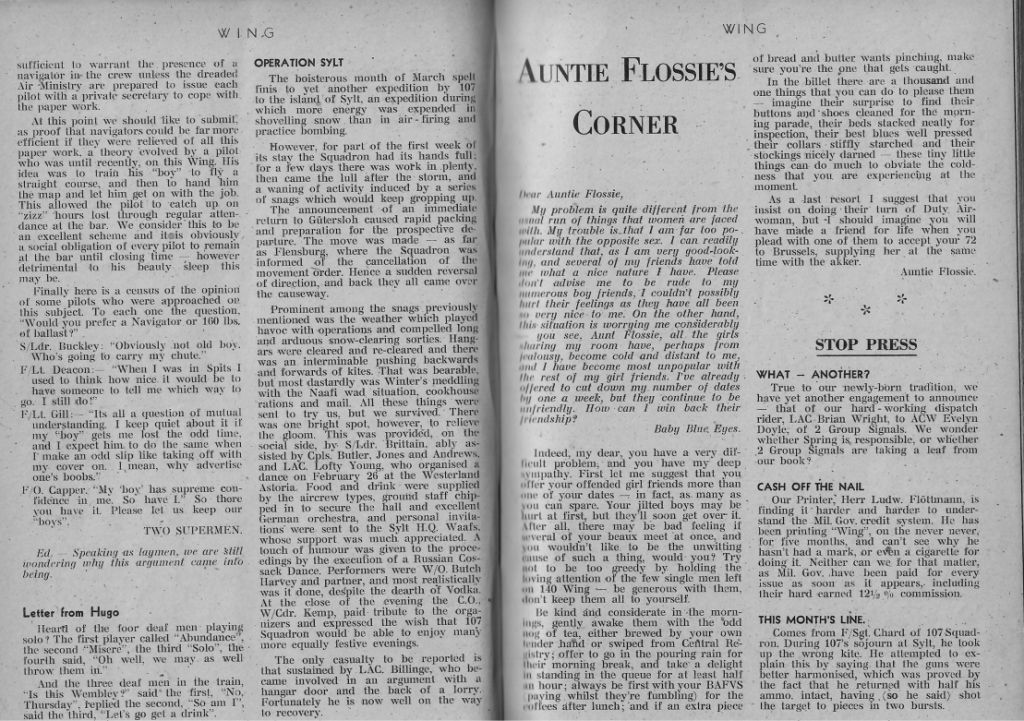

Amongst Don’s memorabilia were two photo albums of photographs taken during his RAF years, many of which are reproduced below. As appropriate Don has been circled in red.

It seems there were some good officers however, as by the end of the month “Chiefy” had put him down for a GH course at Swanton Morley in Norfolk as he thought he would be fed up with tent life. He was there for 5 days which he thoroughly enjoyed. This was formally No1508 Blind/Beam Approach Training Flight Swanton Morley.

Don was back at Lasham on 8th April 1944. On the 7th April his unit had been renamed No 6107 Servicing Echelon Lasham Hampshire, along with Swanton Morley. This is the first mention of 107 Squadron. At this time Don had a few weeks of various bouts of ill health mainly pain in his leg, a sore arm and many nose bleeds which necessitated many trips to SSQ which I presume was the section sick quarters. The nose bleeds were to feature off and on for the rest of his life.

In July he was posted, with two of his pals, to No 6305(Polish) Servicing Echelon, Lasham, the first mention of 305 Squadron, still based at Lasham. Until 305 Squadron moved to France in November, there was a lot of ‘toing and froing’ with some short temporary postings back to 107 Squadron and moving between Lasham and Hartfordbridge.

During July 44 there was a lot of bomb damage at home, and on 23rd September 1944 there was a tragic plane crash at the squadron.

October 1944 it became clear they would be posted abroad and on 12th October 1944 Don wrote his will and sent it home to be opened if necessary, which I found very moving. After much toing and froing packing up and preparing to leave he finally flew in a Dakota to France near Epinoy on 19th November 1944 which he found very exciting. He remained with 305 Squadron until being posted to No 6021 Servicing Echelon, Melsbroek, Belgium on 5th August 1945.

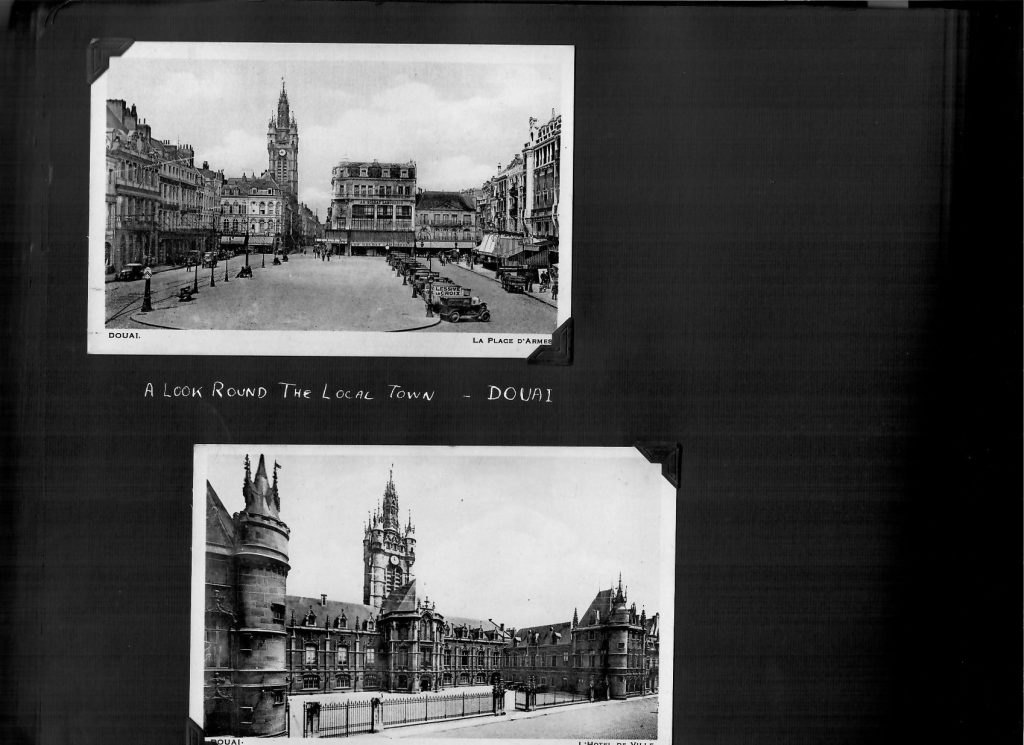

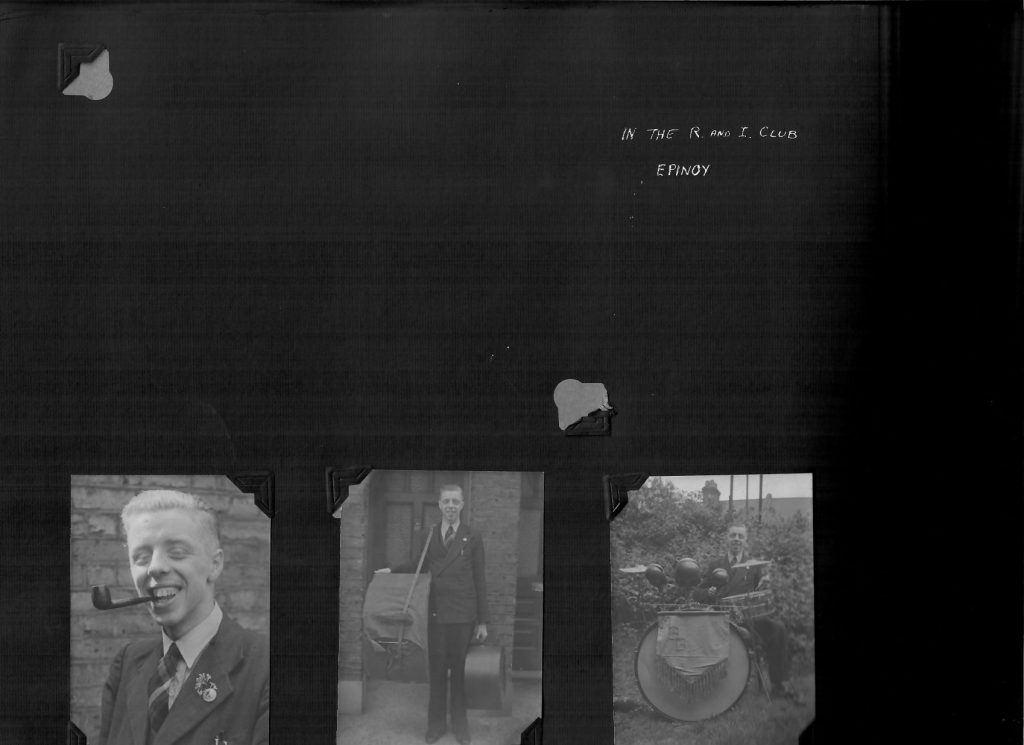

Upon arrival in France, Don immediately went out to see the night life in the nearby town of Douai and discovered a café with a live band where he soon struck up a friendship with some of the musicians, Mr & Mdme Coupez.

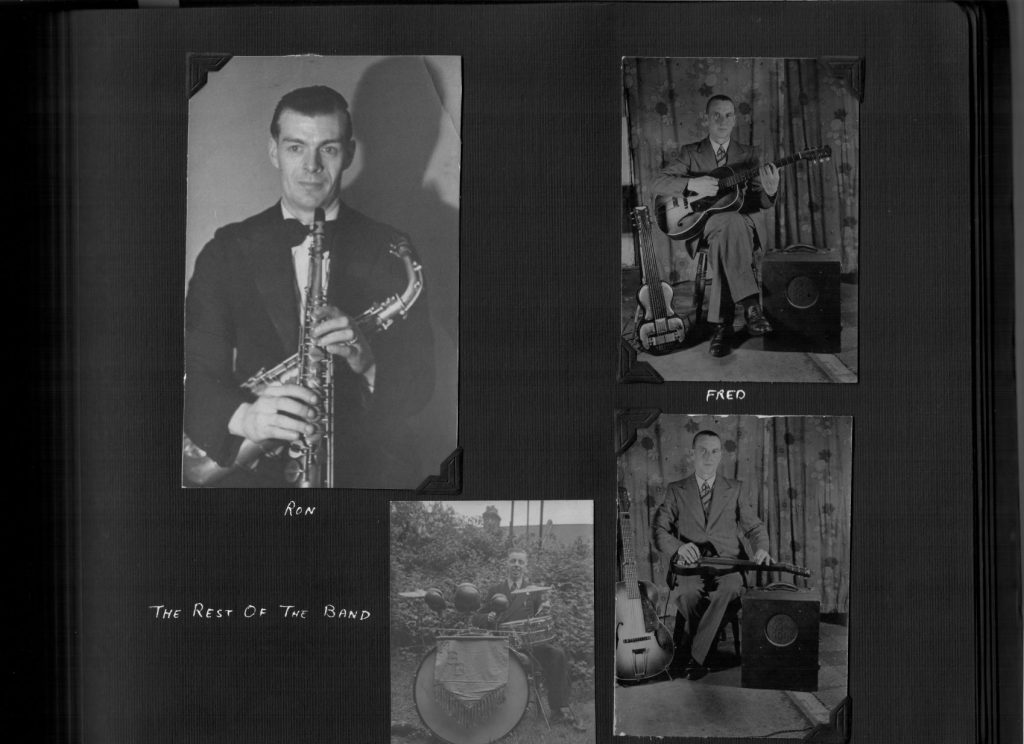

He often played at the café and they were delighted to hear new music which had not been available to them during the war. He also enjoyed many meals with the Coupez family and other locals. Music was very important to him whilst abroad and he was thrilled when he saw the Squadronaires.

On 18th December there was a tragedy on the base when 2 Marauders crashed ‘killing 10 blokes’, during the clearing up Don commented “Thank goodness I didn’t go as a navigator after all”. The German advance was also getting close to them, and arms had to be carried at all times.

Christmas Eve 1944 he enjoyed a very good Polish meal at the 305 mess supper. The entertainment in general seemed to be better abroad, he noted how much he enjoyed the Gang Show No 5 on Boxing day. He was also active in trying to start a 7 piece band and dancing lessons. In March he won tickets to the England – Belgium football match in Brussels which he greatly enjoyed. He then had tea at the Malcolm club* and an ice cream sundae in a parlour, a tram ride and finally saw several English news reels in a News Theatre.

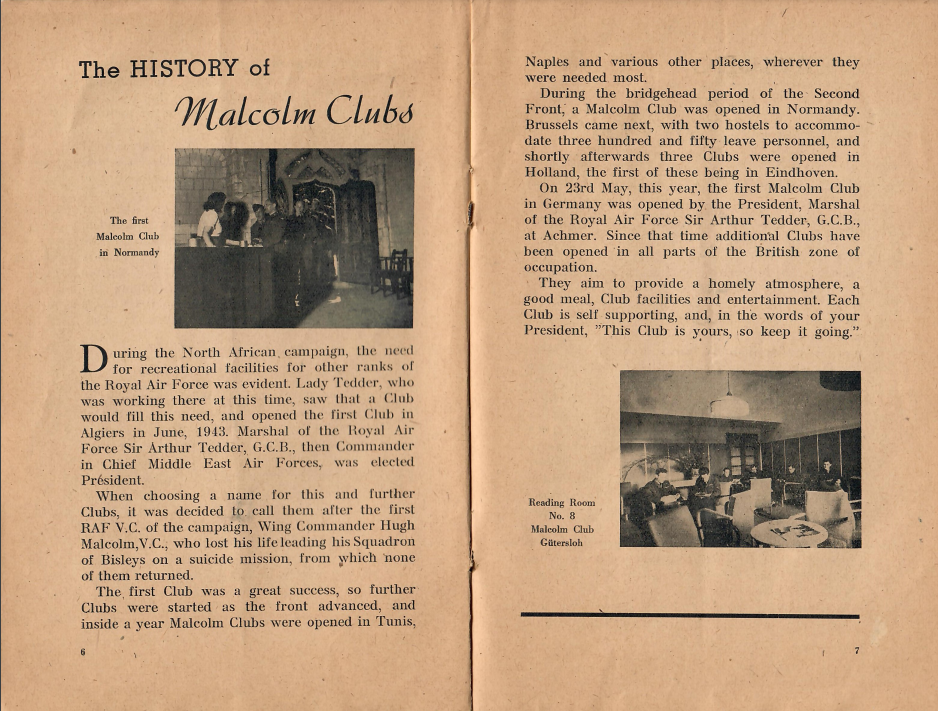

Malcolm club* The clubs were named after a gallant young Scottish Wing Commander, Hugh Malcolm, who had been awarded a posthumous V.C for operations over Tunis. The first Malcolm Club opened in Algiers during 1943 and they soon increased in number with clubs in locations all over the world. The clubs provided not only food but also books, wireless, comforts and a cheery atmosphere in which aircrews could relax. Airmen regarded these clubs as their own

In early January 1945 the MO admitted him to the SSQ for a few days with tonsillitis, he was let out at 10am on the Sunday, had lunch at camp and was then told they were going to dinner with the Pianist in the café band. He had a wonderful meal but could hardly move at the end.

In January 1945 he passed his LAC and became a Leading Aircraftman. However heavy snowfall made life hard, but it gave him more time to organise the music for the band he was involved in trying to set up. He also managed to arrange for a café to do his washing, but then it was lost, but it turned out ‘Whizzo’ in the end. He also started to play with bands in Douai and Epinay. Another bright spot in January was that some officers who had been at Swanton Morley where he had eaten the best food in the RAF, came over and revolutionised the mess.

I had not been aware until reading it in the diary that leave dates were decided by a numbered draw. Don did not do very well.

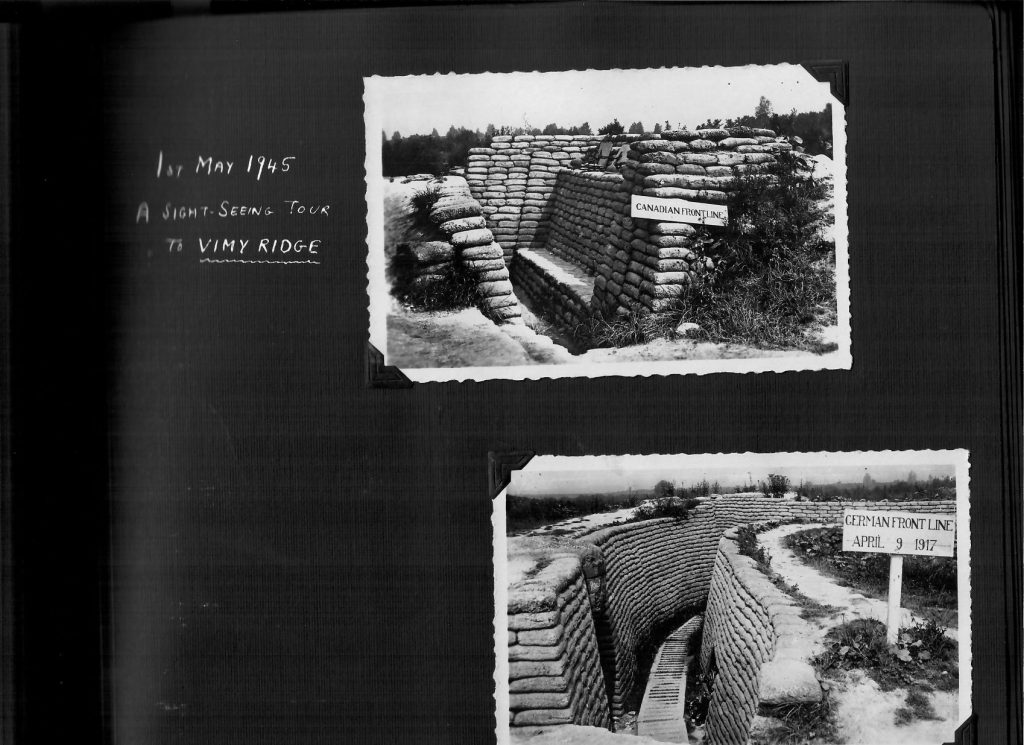

1st May 1945 trip to Vimy Ridge on a Signals organised run.

Then on 4th May there were wild scenes in the billet as they learnt that the war was over as far as their drome was concerned because the remaining fighting was too far away after all the German forces in NW Germany, Holland & Denmark surrendered and then VE Day on 8th May was also well celebrated on the drome.

By 17th May Don was once again considering further EVT (Educational and Vocational Training Scheme) and went to see the education officer before deciding to take the Forces Prelim Examination hoping that the institute of Chartered Accountants would accept it as excusing their Preliminary exam.

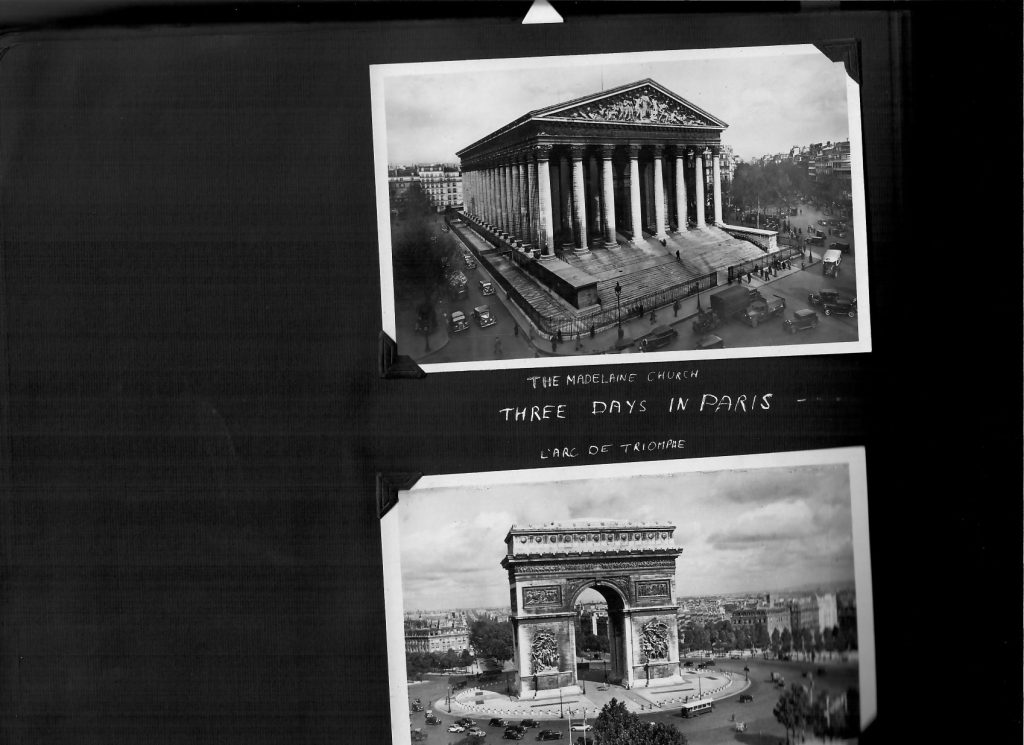

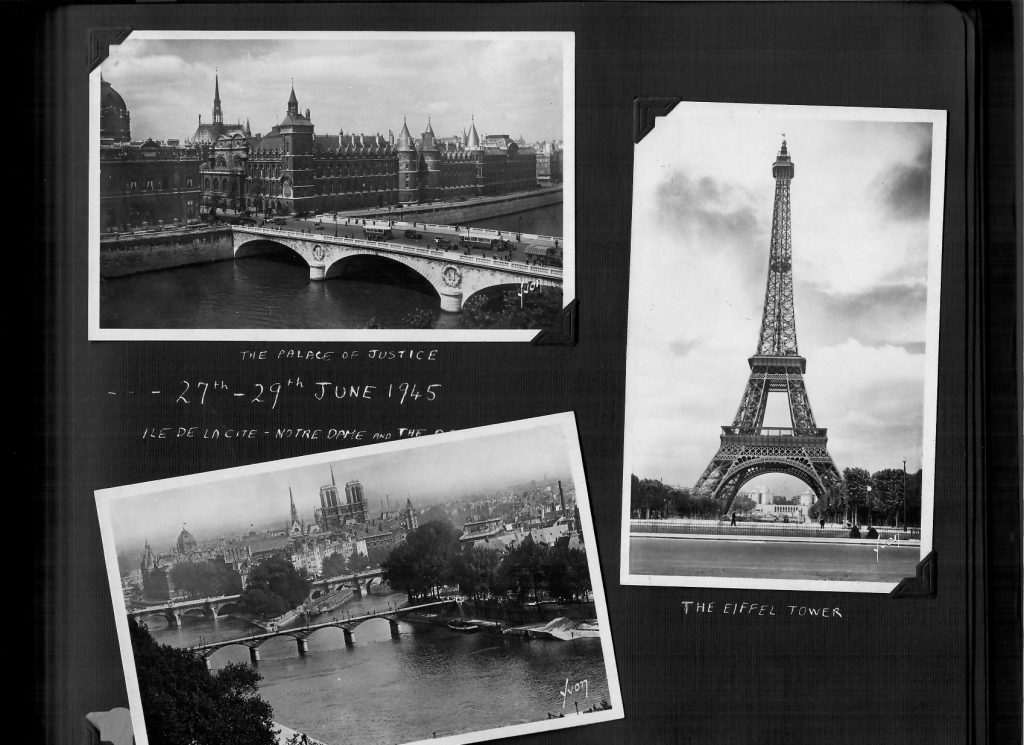

In June he went on a 3 day trip to Paris. Lots of good food, sightseeing, entertainment and comfortable beds.

Even after VE day they were various mentions of further inoculations.

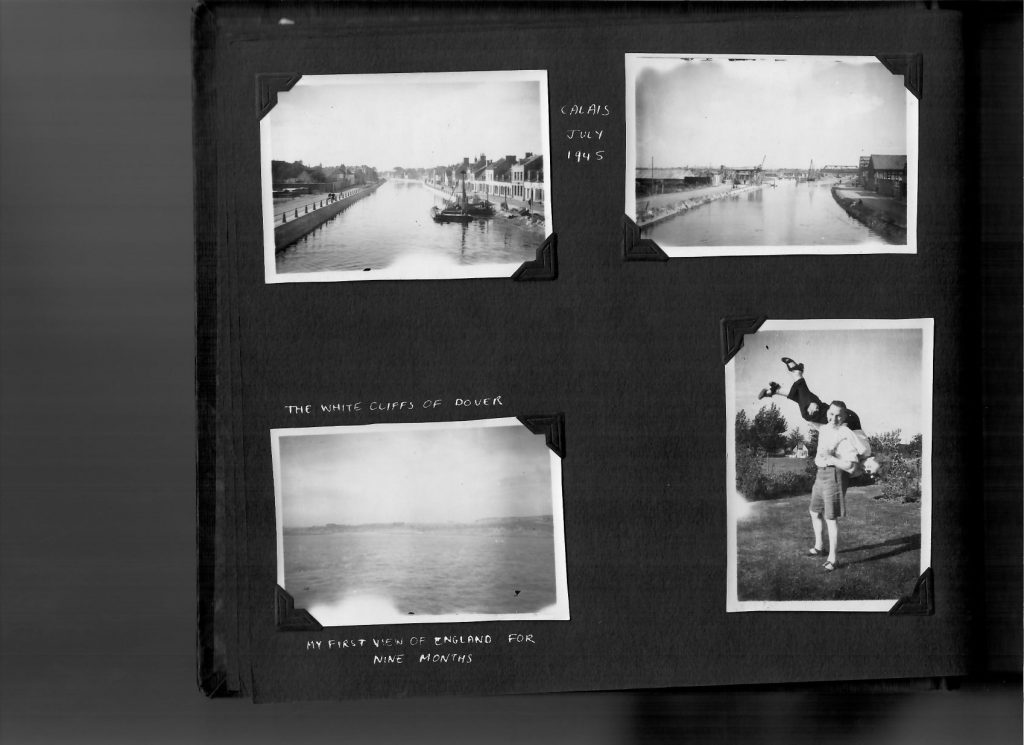

July 1945 he finally went on leave, it was a long journey by train and ferry.

He made the most of it seeing family and friends, and his band The Melody Makers, going to the theatre, to Southend, to Laindon etc.

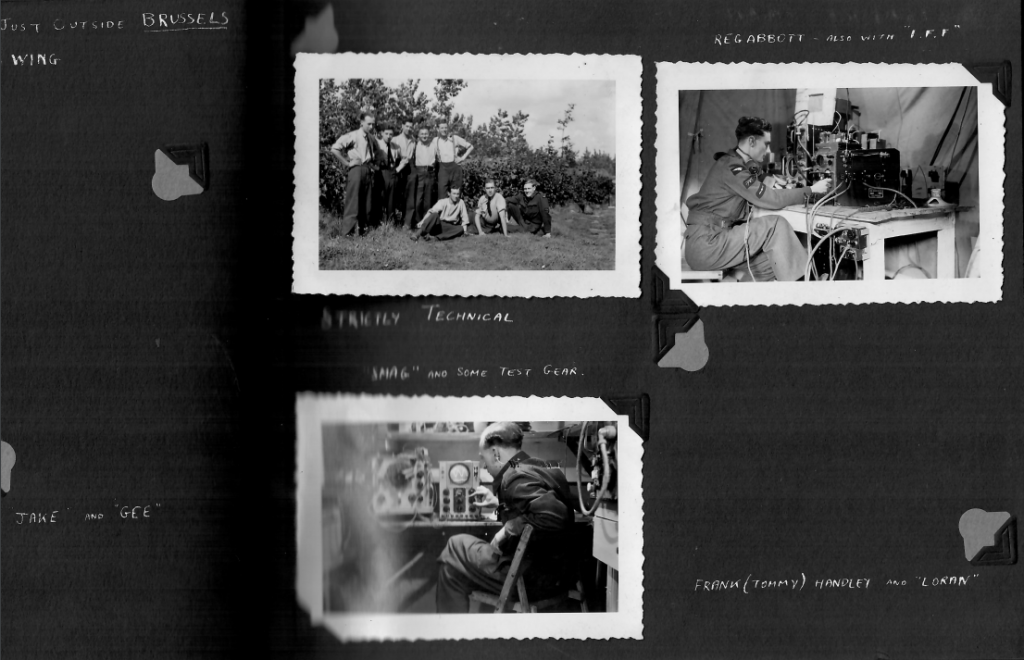

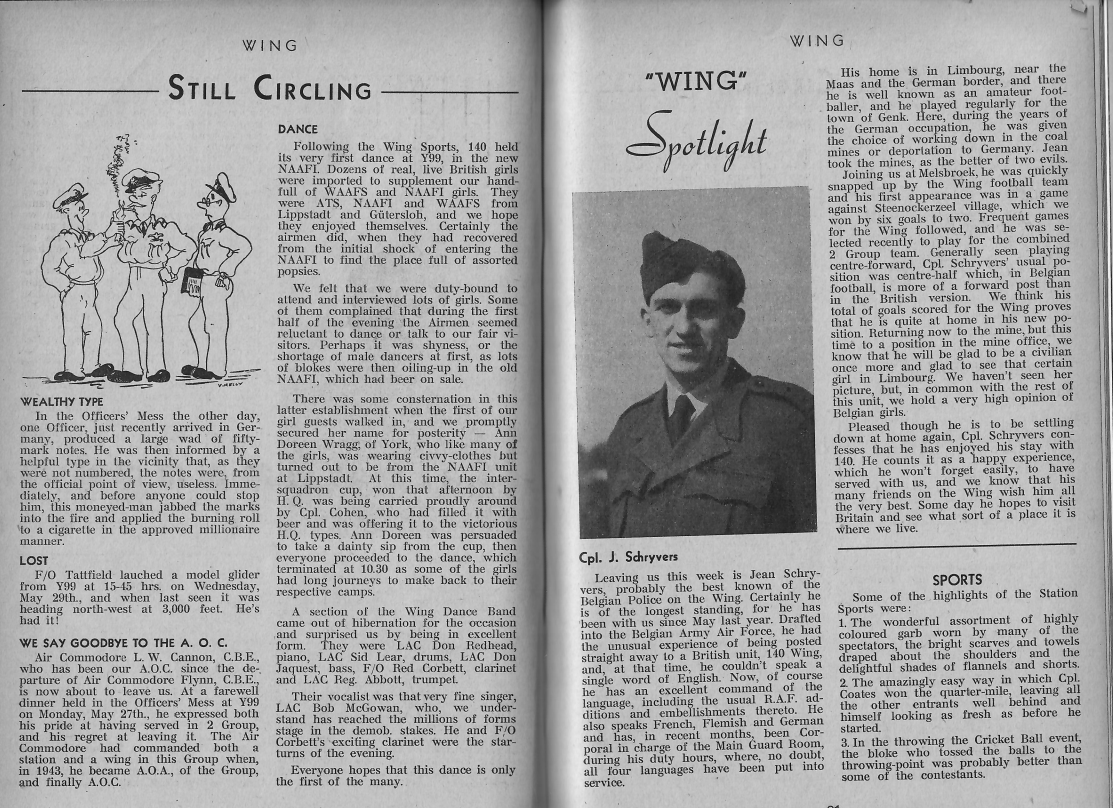

He arrived home on Wednesday 18th July and after 3 extensions to his leave did not have to go back until 31st July. When he got back to camp on 2nd August he knew 107 were leaving but was shocked when he found 305 had left as well. Don had been posted to No 6021Servicing Echelon, Melsbroek, Belgium. Melsbroek is just outside Brussels, and he was part of 140 Wing. 107 were also there so he knew a lot of others.

The group photo above has written on the back “Some of the Boys, Smag, Cpl Jimmy, Jim” and the 3 sitting “Ed, Sgt Mike, Ken”.

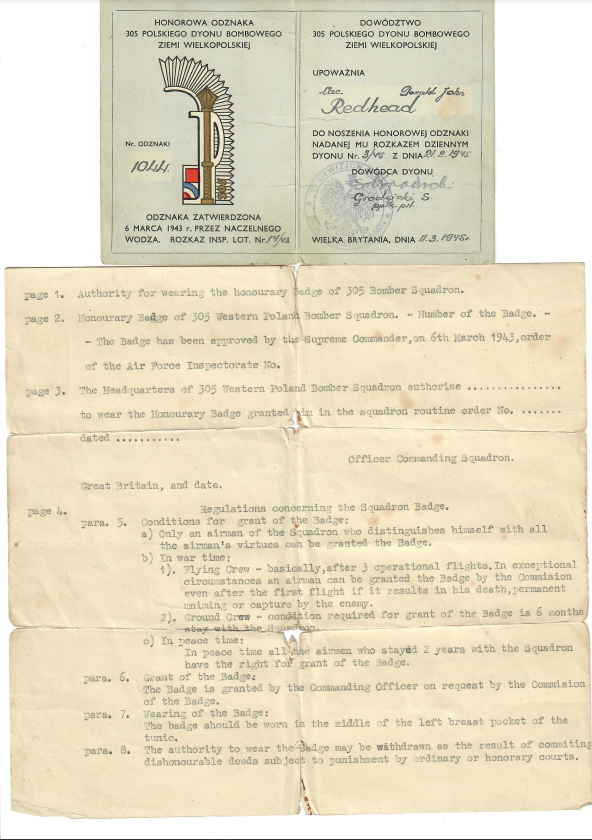

Don always had very fond memories of the Polish aircraftmen he was stationed with in 305 Squadron. He often talked of their bravery, hard work and good humour, and how he tried to advise any who discussed whether to go home at the end of the war not to go back to Poland, and how he then lost touch with them. He also often told the story of travelling home on leave and being stopped by an officer who berated him for being improperly dressed because he was wearing a Polish insignia. He of course argued correctly that he would be improperly dressed without it as he was attached to 305 squadron. It was just another example to him of the stupidity and short sightedness of some officers. From that time on he carried the note below confirming his authority for wearing the honorary badge of 305 Western Poland Bomber Squadron.

More photo’s from Melsbroek of various Aircraft

He took trips to Brussels and Bruges in August.

In September they were being plagued by mosquitoes but then were able to move out of tents into a hanger which was ‘wizzo’.

By October ‘45 they got some news about the demob which he was very unhappy about ‘absolutely bloody awful’. Once the war ended Don wanted to be demobbed asap and to get on with his accountancy studies.

Don noted on 13th October ‘We had a prang on the drome tonight’ which was a terrible loss of 30 lives to happen now.

He was due to go on leave in October but it was put back over a week by a terrible gale. There are some photos with his parents in their garden in Plaistow in November.

However this time he was aware that he would be returning on 15th November 1945 to Y99 Gutersloh Germany. The billets were good with central heating, but then the coal had not been ordered and they had a few grim days with no heating.

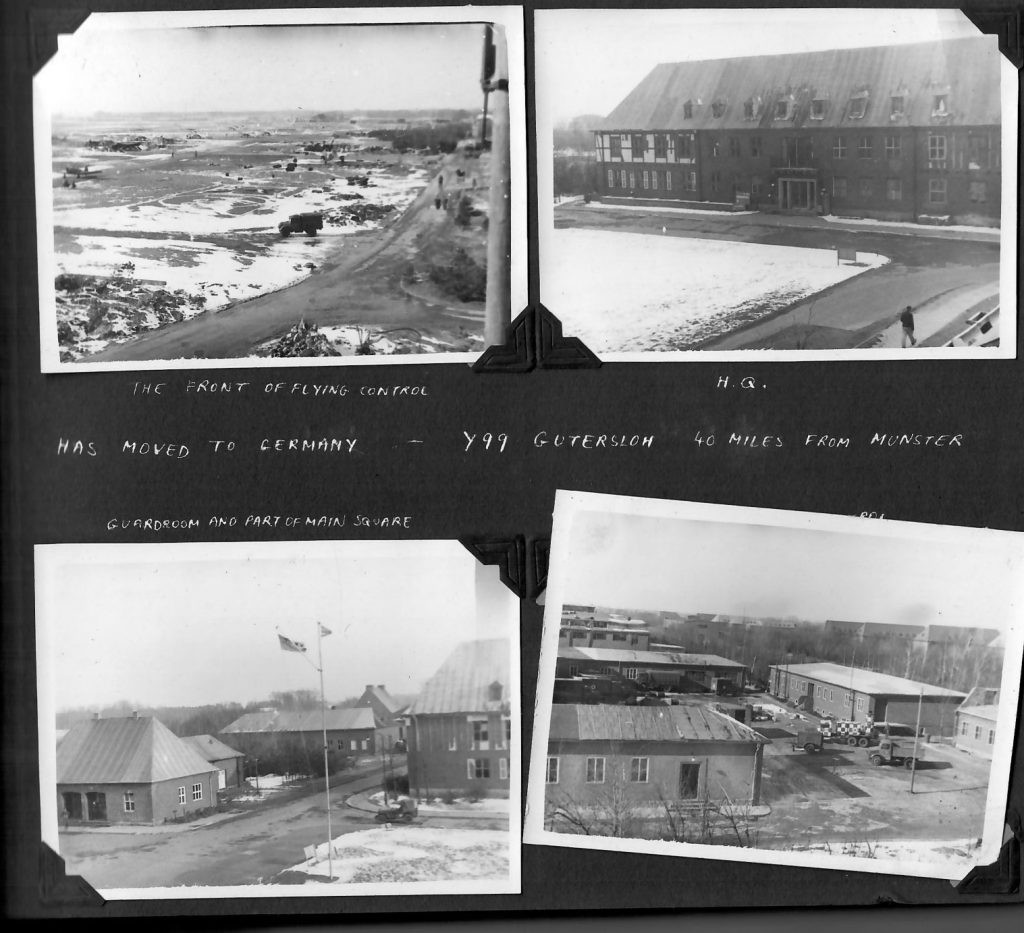

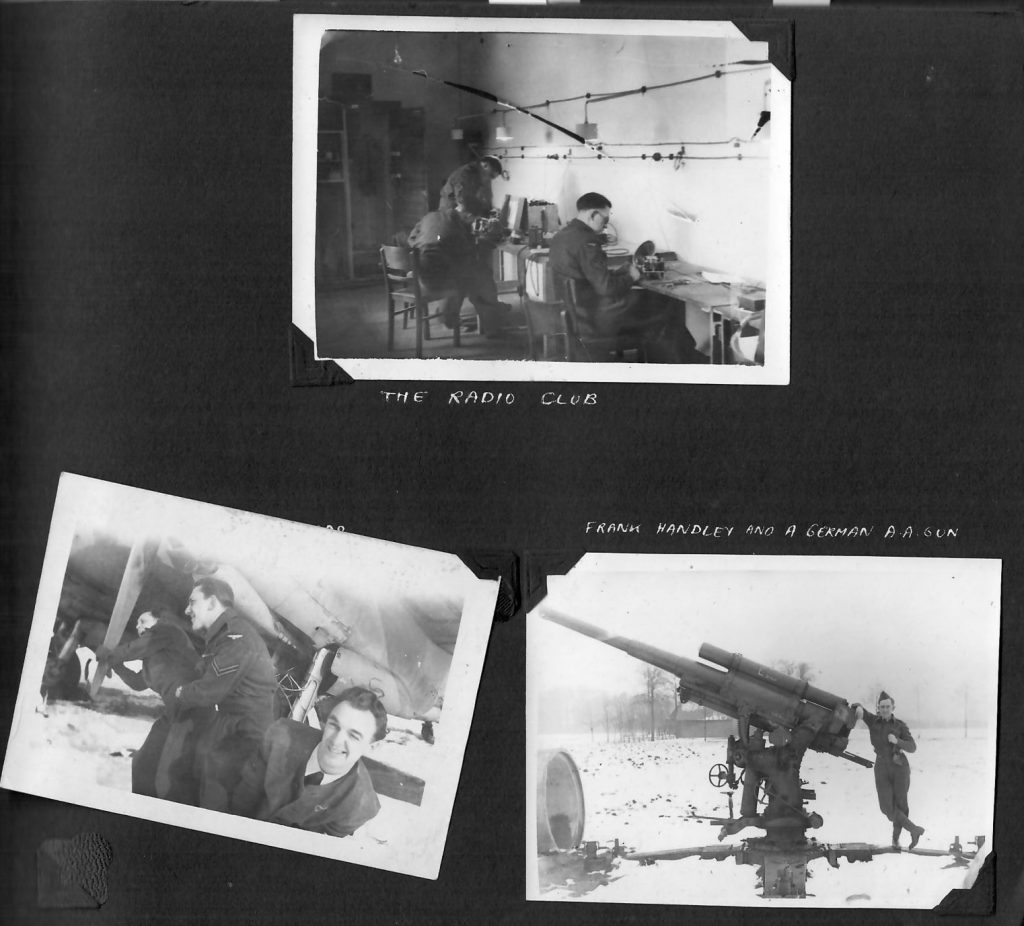

Below are photo’s from November 1945 of Gutersloh and the Radio Club

The Malcolm club in Gutersloh was approved of as was the Adastral theatre for classical music concerts, and he immediately set about trying to set up a band, but he had a miserable 21st birthday. His family had a little ‘do’ for him during his next leave in March.

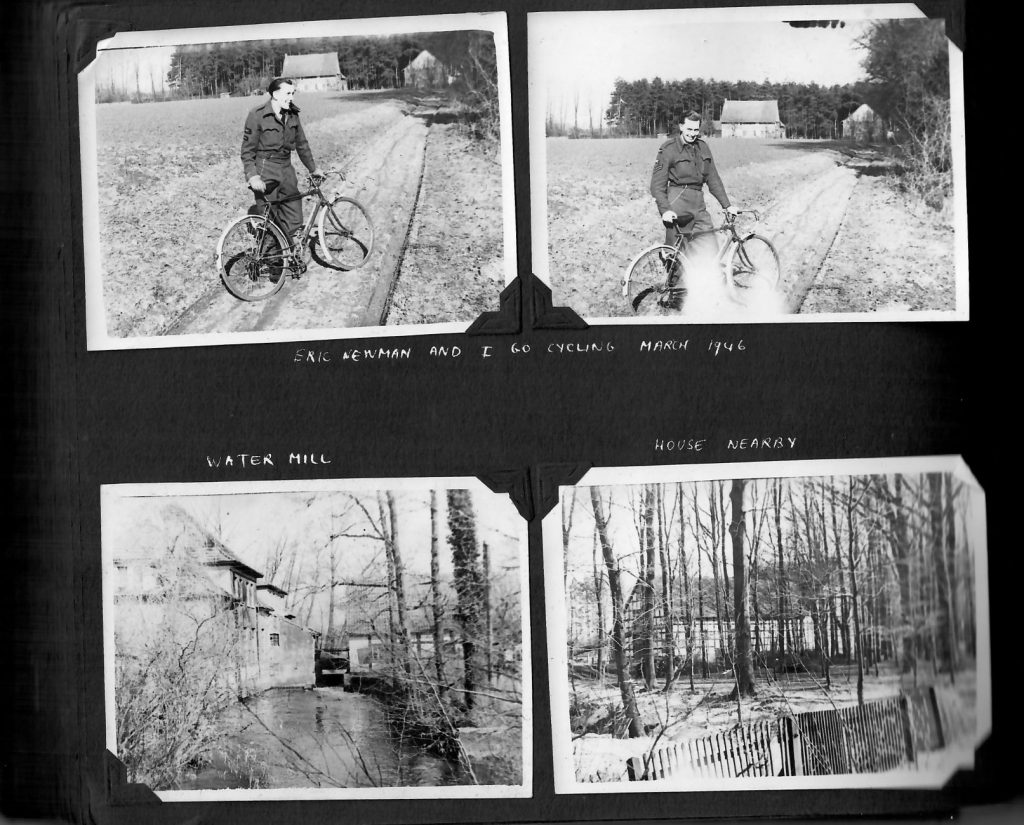

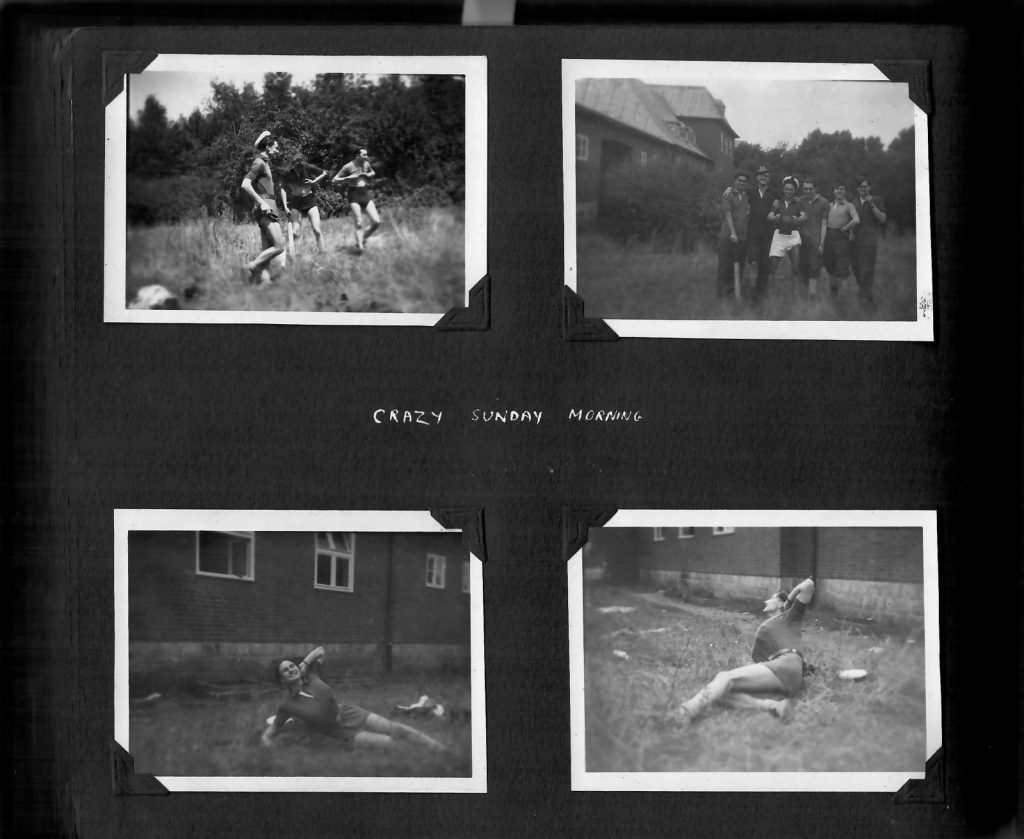

Don spent 18 months in BAFO Gutersloh until he was demobbed in May 47. Below are various photographs of this time.

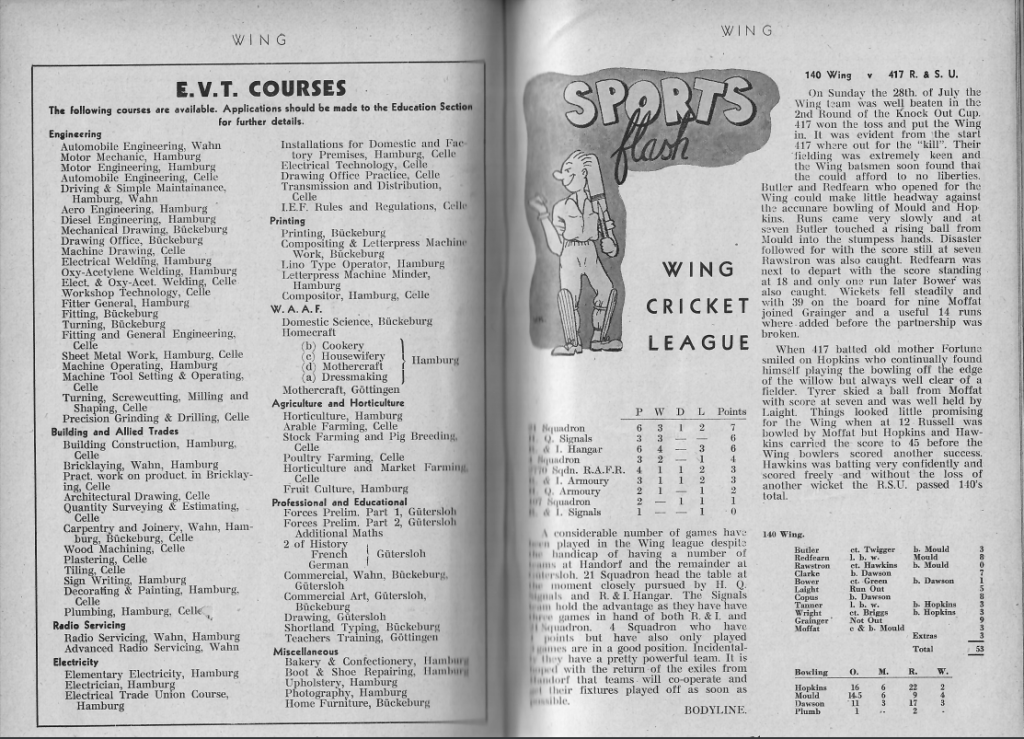

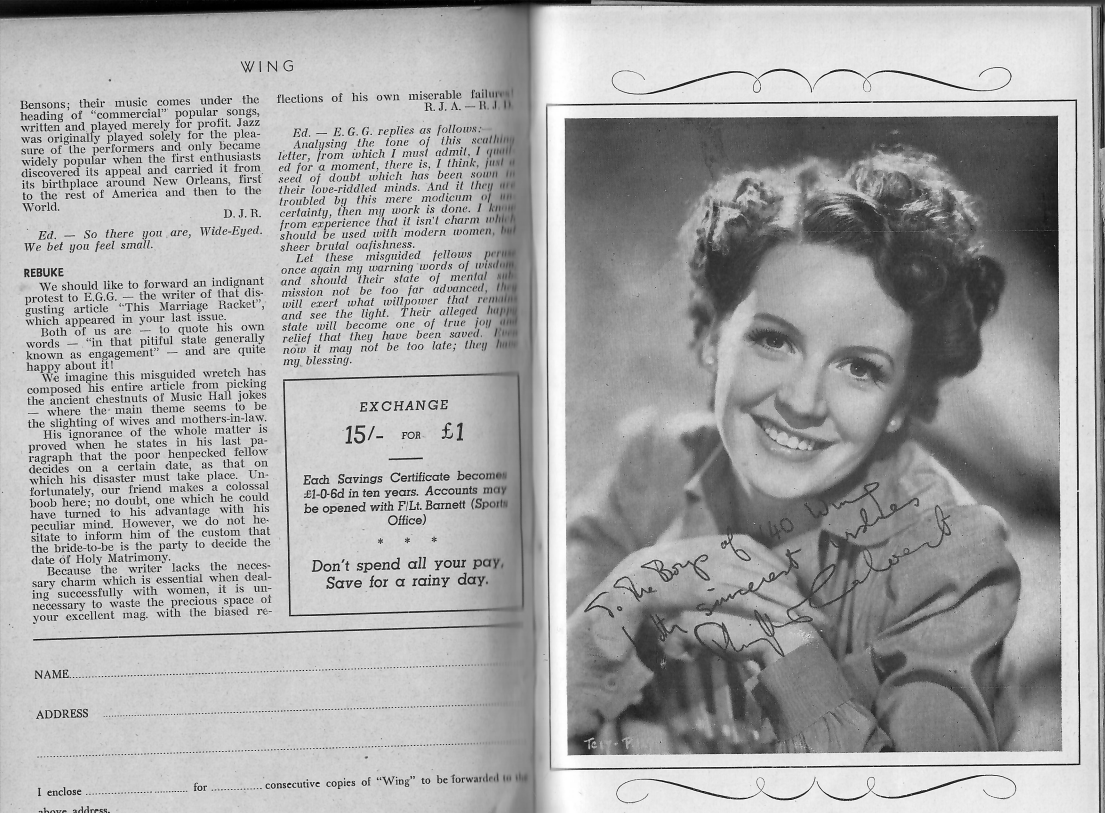

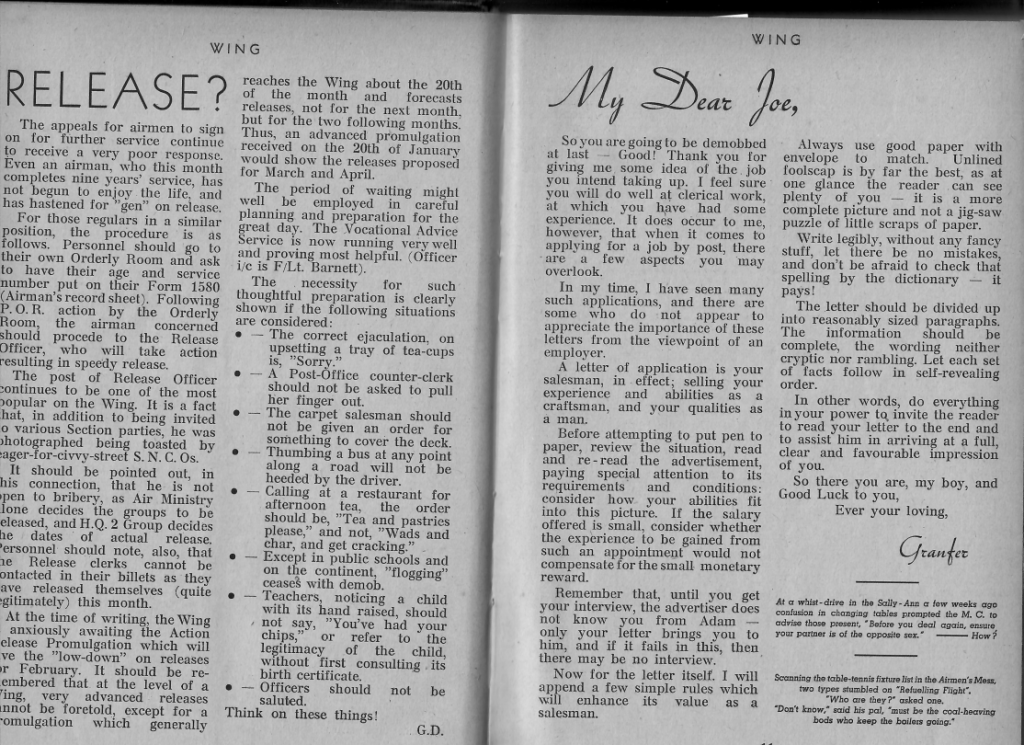

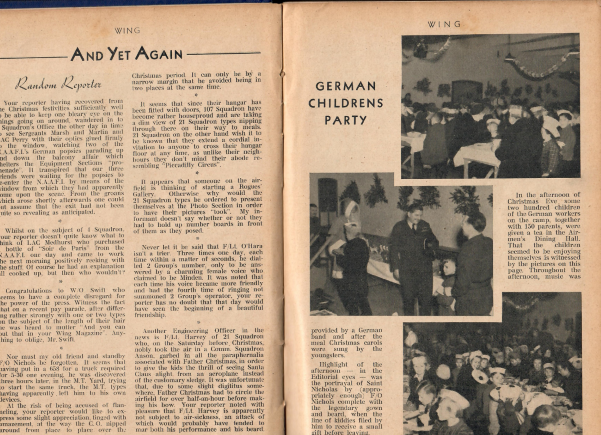

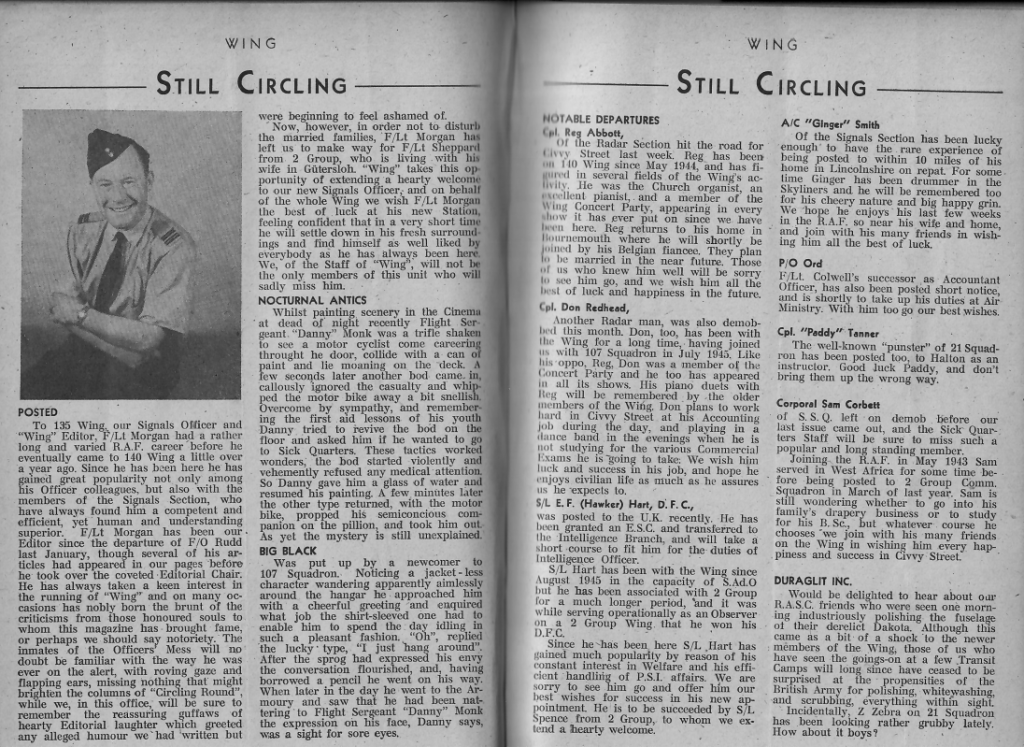

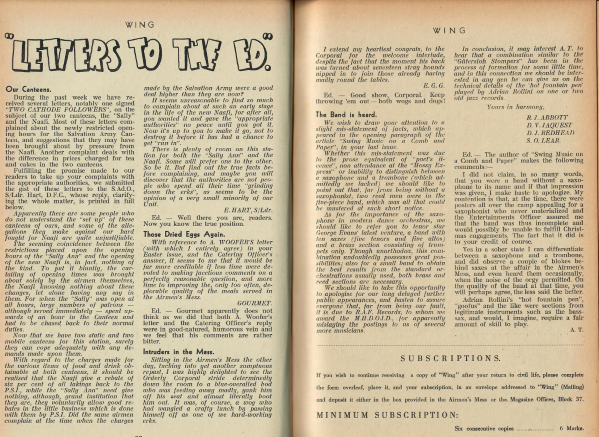

Wing the magazine of 140 Wing, B.A.F.O. (British Air Forces of Occupation in Germany) was first issued Christmas 1945 and monthly thereafter, farewell edition November 1947, when the Wing was disbanded Don had all issues bound into two volumes and they have proved to be a wonderful source of information for me about his time in BAFO Gutersloh. Various articles will be reproduced below.

Wings Vol 1 No 2 January 1946 Article on 6021 Radar Section

Very little information is given about his work but he clearly spent a lot of time on music, shows, EVT etc and also spent a lot of effort ensuring he could partake in all these activities rather than working!. He resumed EVT almost as soon as he arrived in Germany.

Wing’s first edition Christmas 1945 contained an article on EVT

Don was also was very quick to get involved in starting up a band and organising the Christmas Concert, The Mozzy Express on Christmas Eve, which got a good review in Wing Vol 1 No2

By July they wanted to put on another concert and there was a request for talent in Circling Round. Wings Vol 1 No 11

Don got a further mention in the same edition with regard to having to move Billets. REMOVALS

Photo’s of the Billet

The band went fairly well and Don got more into the saxophone and decided to play that instead of piano partly because of a lack of Saxist to play in the band. Wings Vol 1 No 3 . On the same page is a request for help with another Concert Party.

In Wing Mag Vol 1 No 6 May 1946 Don and friends from the band had a letter published in response to some previous criticism. The Band is Heard

Don recorded in his Diary on 25th May 1946 that he played in the band at a dance and it was ‘A wizard success’. Wing magazine gave a good review in which he was named Wings Vol 1 No 8 and there were 3 letters in letters to the Ed in the same edition – Our First Dance,

Further letters about the dance were also in the next 2 editions Vol 1 No 10 & 11 Our First Dance Again and Dances.

September and October Don seemed to be busy and enjoying playing at dances including the Sargent’s Mess Dance on 28th Sept and the mess dance on 2nd October. Wings Vol 1 No 15

Don was very pleased to get a letter printed in Wing Vol 1 No 15 19th October 46 issue regarding the ‘The inside on Jazz’ in response to a previous letter.

Wing Mag vol 1 No 17 November 30th gives a review of Bandbox in which Don got a special mention for his piano playing.

There was a small mistake in that it stated this took place on 11th October but Don was on leave at this time but he does mention the event on 14th November. Then F/O (Flying Officer) Rae gave Don the job of putting together Bandbox 2 for Boxing Day. He was very pleased with the shows reception and Wing Magazine Christmas 46 edition gave a very good review giving Don a mention by name for his piano playing.

On 3rd August 1946 Don noted he had been put on recording inventories of the houses being requisitioned and wrote “Horrible job made us feel a lot of heels when women started crying.” The August edition of Wing Vol 1 No 12 had an interesting letter and response about this “controversial subject”.

Don continued to be unhappy with the demob process and caused upset by contacting his MP Elwyn Jones and on 26th November 1946 his response caused a “colossal stir” at the base. Demob was a big issue in the Wing Magazine. The first edition contained an article entitled The How Of Release and Resettlement and the second edition contained the article Release?

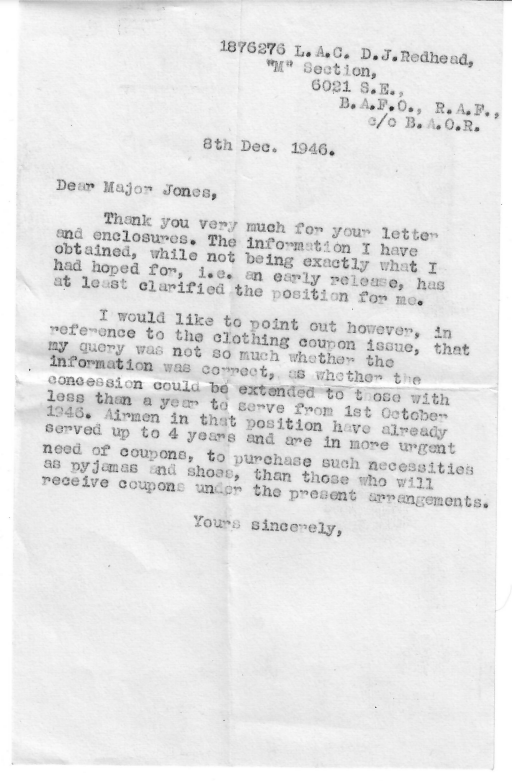

He kept a copy of a letter he sent to Major Jones on 8th December 1946 about the demob and clothing coupons – Major Jones Letter.

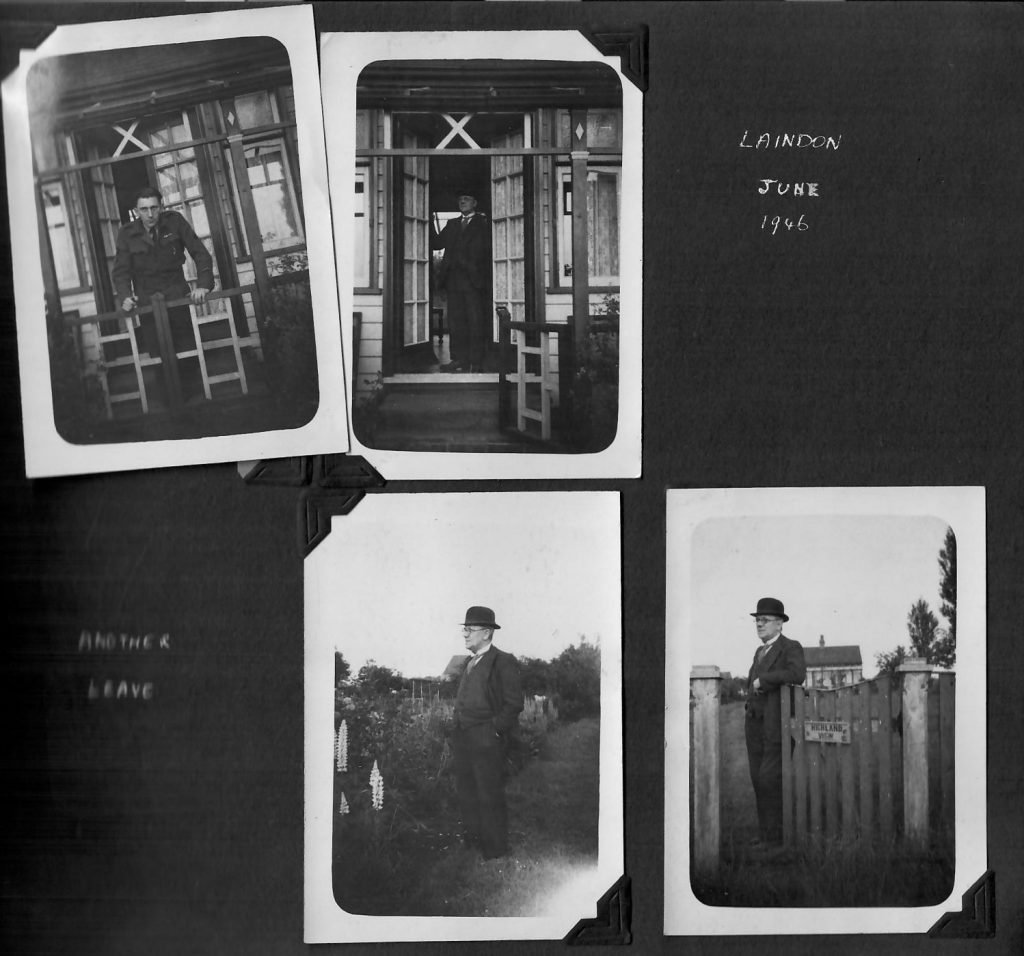

Don had two weeks leave in early June 46 and was at home to listen to the Victory Parade and saw Gloster Meteor jet aircraft fly over. He also spent some time at the family bungalow in Laindon and took the following snaps.

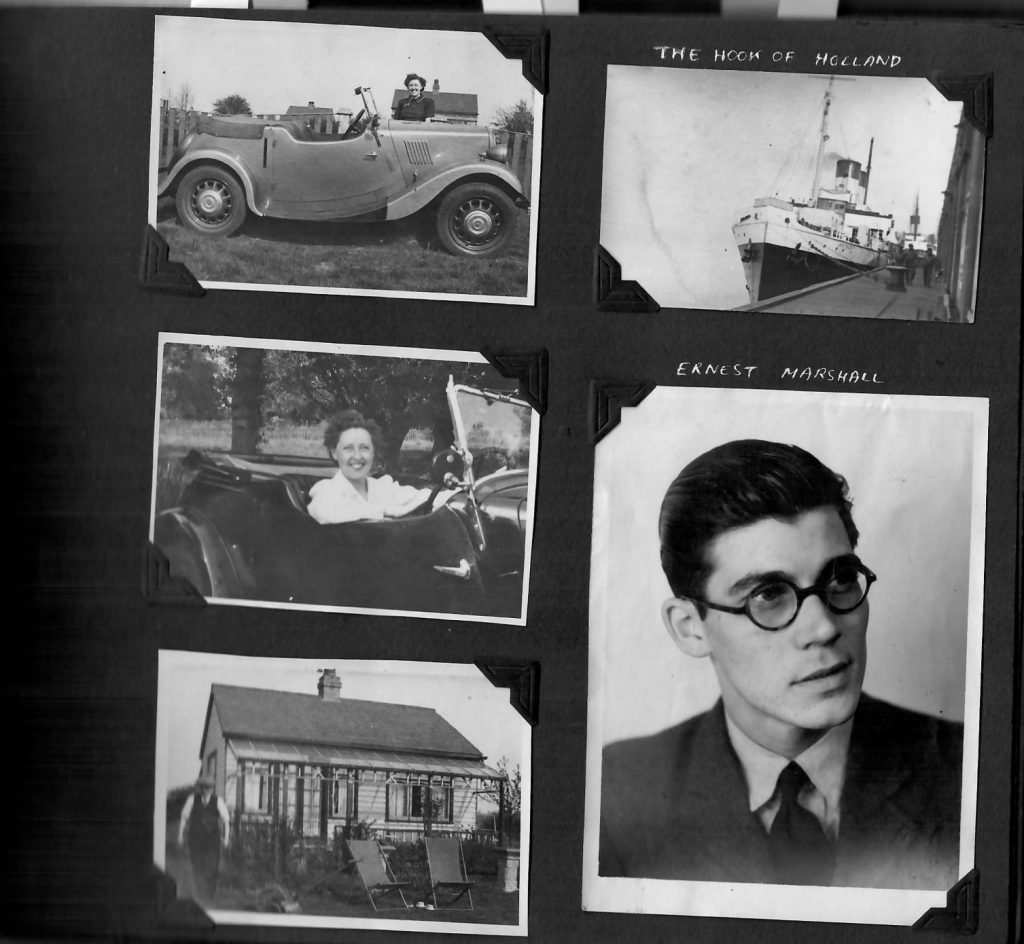

Not sure why his father was wearing a bowler hat and the cars would have been his brother Walters as he owned a garage. It would appear Don’s father bought the bungalow partly to escape some of the bombing and with a view to retiring there. I don’t know why this never happened, but it was sold soon after the war ended.

In Sept 46 Don was sent to Manston for a couple of weeks as part of the ongoing victory celebrations. He was excited to fly again in a Dak (Dakota) to Manston and was able to spend quite a lot of time at home during this period.

NB interesting article in Wing Victory Number re The Wing at Manston Victory flypast June 46

and photo taken at Wahn waiting to Fly to Manston.

His elder brother Walter remarried on 12th October and Don managed to get leave for this event.

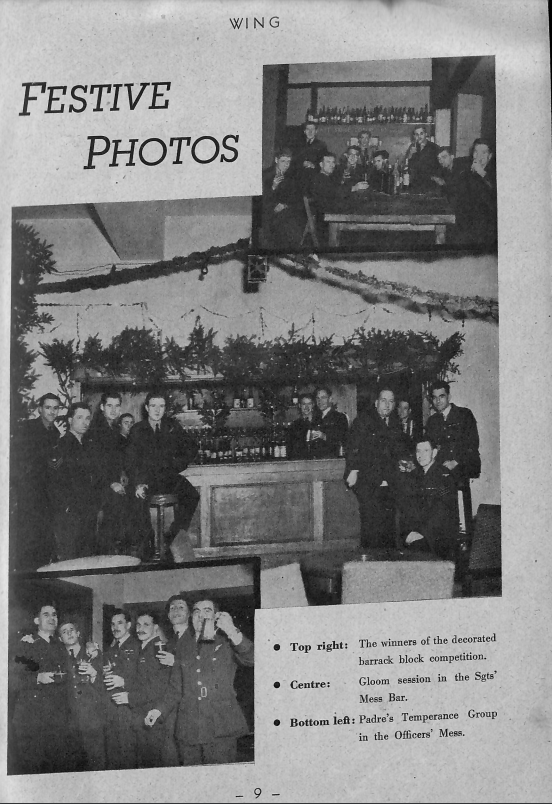

His second Christmas in Gutersloh was extremely busy. As noted above he was very involved in organising the Christmas Show, Bandbox2, which was very well received. Christmas day Don’s billet won first prize of a barrel of beer in the room decorating competition, they had a cowboy theme and dressed up and had a guitar & voice quartet. They then serenaded the dinner queue. Wing Magazine Vol 2 No 1

He also helped at the German Children’s Christmas Party on Christmas Eve.

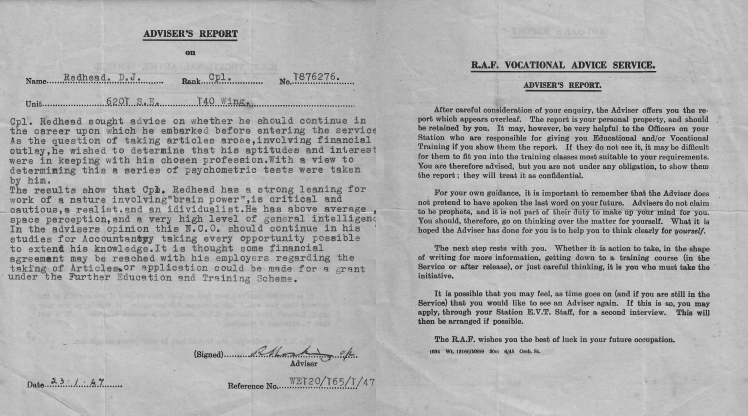

17.1.47 Don went to the RAF Vocational Advice Service VAS at 2 Group. He found the test interesting and the adviser’s report detailed he would be good as Barrister, Accountant, Solicitor or Senior Admin Grade Civil Servant. Advisors Report below .

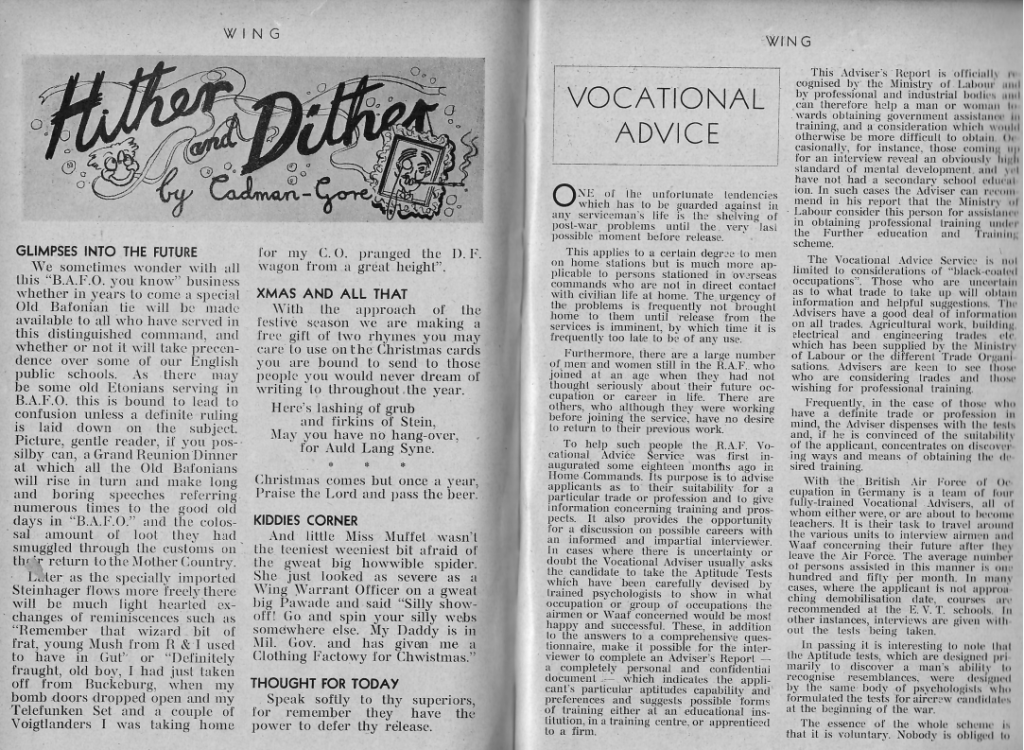

Wing Magazine had an article about Vocational Advice

The following photos were taken in January 1947

Wing Mag Don had another letter published regarding cat calling at the variety shows.

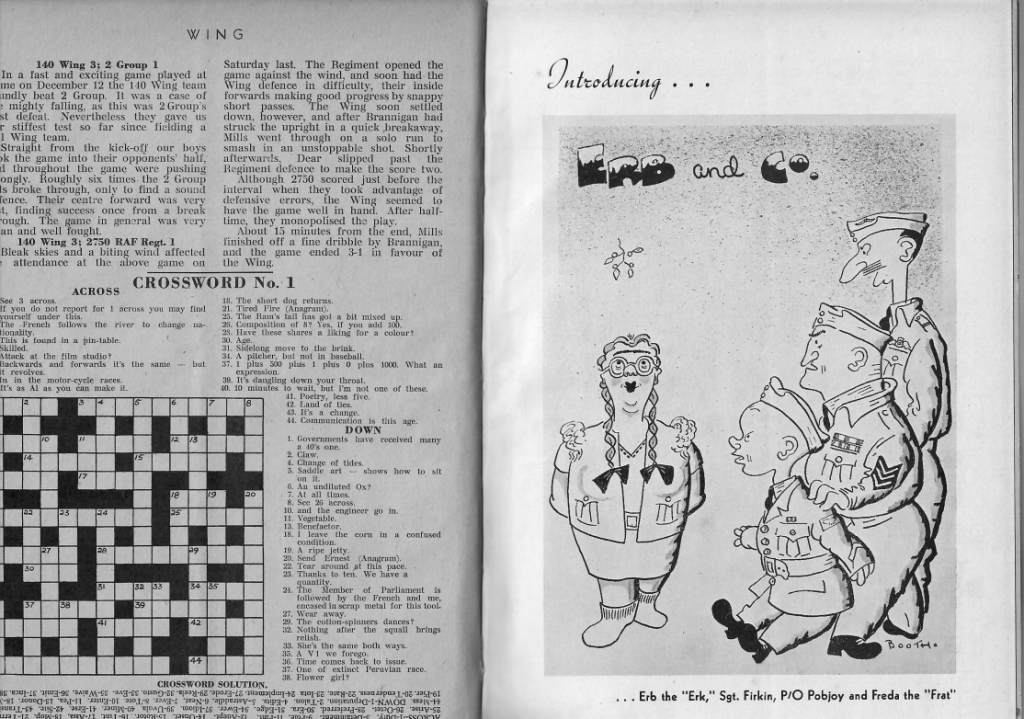

There was a Wing Concert Party show on 23rd February 1947 which was again well received. In one of the sketches Don dressed up as “Freda the ‘Frat’” inspired by the cartoon Wing Mag. The review was good.

Four days after the concert Don was on his way to the island of Sylt. This turned out to be a bitterly cold “journey through hell”, through a blizzard. He was there for nearly a month which he did not enjoy and probably the highlight was on the second day when he wrote “Went for walk in morning, with Hugh Clunes, over to the seashore. I have never before seen the sea frozen as far as the horizon or seen boats frozen in. Quite a scene of arctic desolation.”

Don was very pleased to get back to Gutterslosh on 23rd March. This was written about in Wing Mag Operation Sylt.

A couple of days after getting back he went on leave until 15 April 1947 and spent the next two weeks getting ready to leave for good.

Don left Gutersloh on 1st May 1947, arriving at Hull 2 days later and then on to Lytham for his last 2 days in RAF. He arrived home at 10pm on 6th May 1947. There was a lot of release paperwork to complete and a lot of ‘waiting around’ that “I got really cheesed, despite the fact that this should be the best day of my life’ Maybe that is why he kept his RAF Service and Release book.

Wing Mag had a piece about his and his friend Reg Abbotts departures.

Don wrote an amusing play about his despair regarding how long his demob took to come around which I found in his letters note book.

He had time off to rest and go on holiday to Southend returning back to the accountancy office on 9th June 1947.

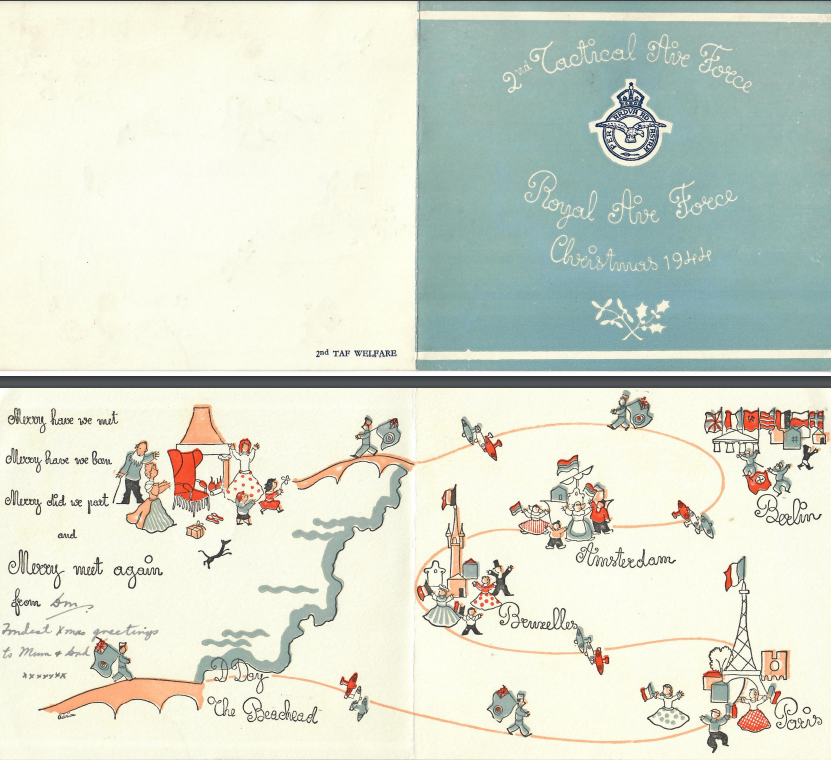

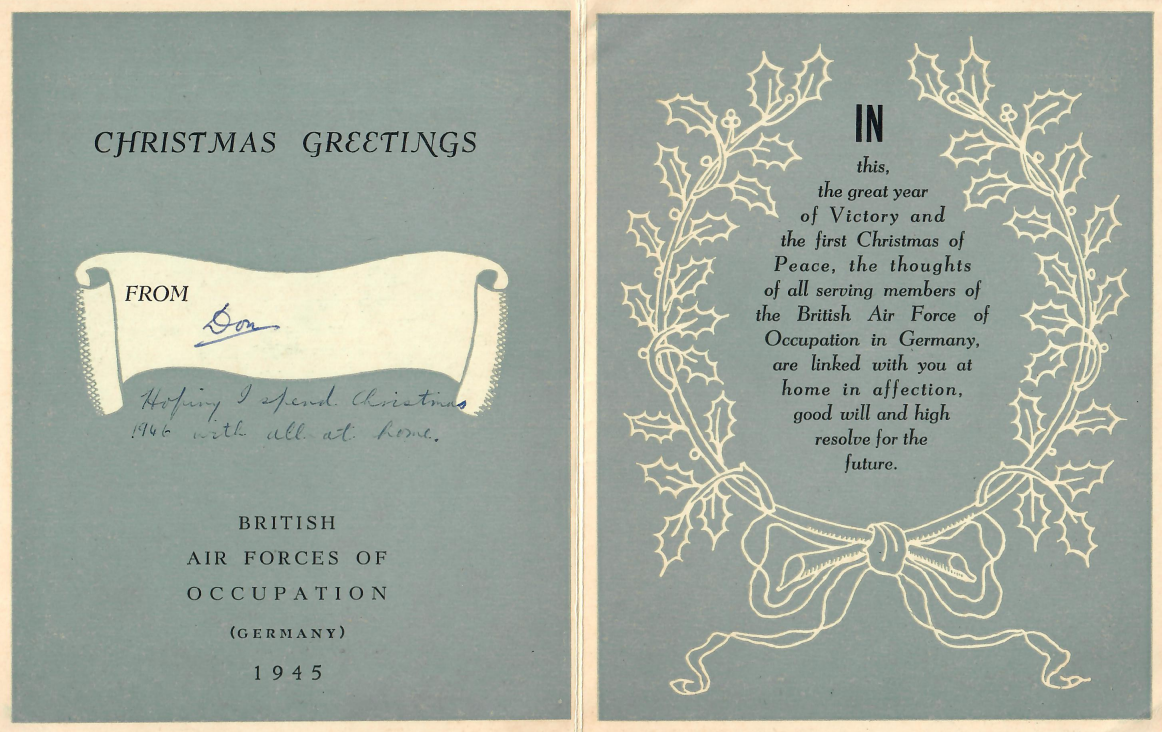

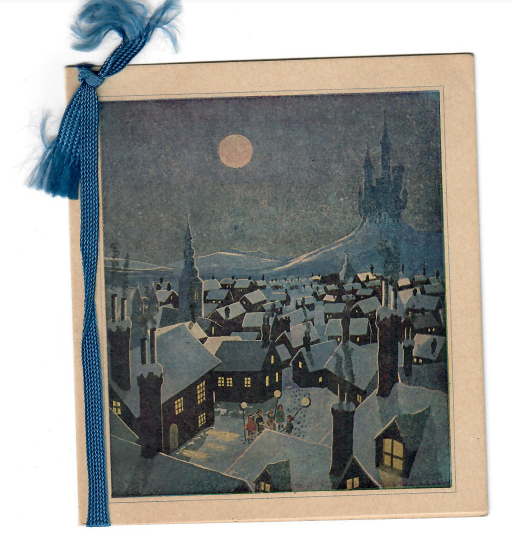

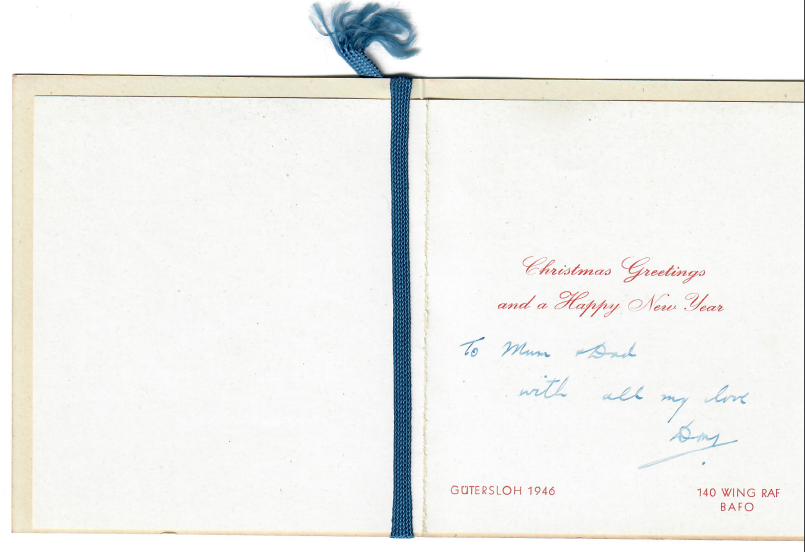

When on active service Christmas cards were provide to send home. Below are a selection I found Don had kept.

No 8 Malcolm Club was at Gutersloh and Don often visited and kept a few of their magazines. Vol 1 number 1 November 1945 included a brief history of Malcolm Clubs.

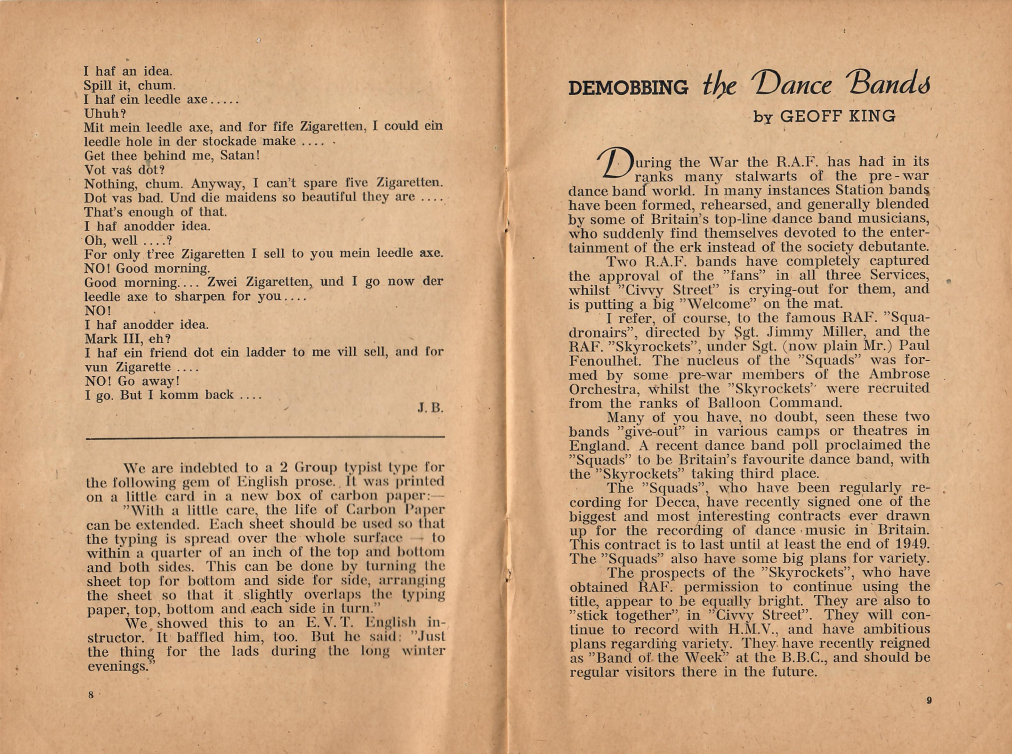

Issue No 2 ran an interesting article on Demobbing the Dance Bands, primarily about the Squadronaires which Don loved to the end of his life. The last concert he attended was to see the Squadronaires at the Cliffs Pavilion Southend the year before he died. The Article also mentioned the Skyrockets which Don was very proud of having played with on occasions at Gutersloh.

Hornchurch

Don married Doreen in 1951 and they moved to Hornchurch in Essex (Now Havering) where they brought up myself and my two brothers and lived for the rest of their lives. He was always interested in the history of RAF Hornchurch, and this was often discussed on our walks at Hornchurch Country Park near the old Airfield. There are a couple of mentions of RAF Hornchurch in his diary’s. Amongst his memorabilia I found various books on RAF Hornchurch and below is an interest article he kept on the history of the station. 63 Hornchurch The Battle Front

One important aspect of the ‘brave history of RAF Hornchurch missing in the article is the heroism of Raimund Sanders Draper(27 December 1913 -24 March 1943). He was an American volunteer in the RAF who when his engine failed just after take off did not bail out but guided the Spitfire so it did not directly hit a school beside the airfield. Only one pupil was slightly hurt. In his honour the school was renamed Sanders Draper School in 1973.

Radar

Don’s training at No 7 Radio School as a Radar Mechanic lasted for 8 Months.

Whilst the studying was at times hard, I am sure he enjoyed it and the knowledge he gained was useful for the rest of his life. He also very much enjoyed the night life and playing piano in his Dance Band during this time back in London, not to mention being able to spend a great deal of time at home.

For obvious operational reasons there is not much detail in the diaries or letters but he kept all the exercise books used during his studies and many text books.

Exercise Books

Small red notebook. Probably exam revision notes

Elementary Radio Notes

Internal Combustion Engines notes

Voltage

Radio and Electrical Notebook No.1.

Radio and Electrical Notebook No.2.

Radio Department Northern Polytechnic Notes on Filing

Soldering

RAF Training of Radio and Wireless Mechanics, Final Examination in Technical Electricity 3rd June 1942 SCAN all 3

Text Books

Handbook of Wireless Telegraphy 1938 Vol 1and 2

Elementary Mathematics for Wireless Operators by W.E. Crook 2nd edition April 1942

Radio Simplified J Clarricoats 1942

Definitions and Formulae for Students (Radio and Television Engineering( by A.T. Starr 1941

Handbook of Workshop Calculations, Board of Education and Ministry of Labour and National Service April 1942

His interest in Radar continued all his life. Whilst still in the RAF he joined the Radar Association and kept all his copies of The Radar Bulletin, the official journal of the Radar Association from Vol 1 no 1 in March 1947 until through to Winter 1972/3 when it had become Radar and Electronics.

Also amongst his collection:

RADAR A Report on Science At War Published in the United States of America by the Government Printing Office reprinted by HMSO, London 1945

RADAR Radiolocation Simply Explained by R.W.Hallows 1947 Edition.

Contained within this book for the Obituary for Wing Commander Edward Barton

EVT

List exercise books.

Royal Air Force Sketch Book Graph book used for Map construction

Mathematics

English Literature – Don wrote an interesting essay titled “One Law For The Rich, Another For The Poor.”

Economics

English

Geography – Europe (2)

Geography – British Isles (2)

He also kept a number of examples of Forces Preliminary Examination papers.

Don passed his Forces Preliminary Examination in February 1946 64 Exam Results.

Information on the Structure of the RAF and Squadrons Don was attached to.

From Wikipedia

The RAF Volunteer Reserve was formed in July 1936 to provide individuals to supplement the Royal Auxiliary Air Force. The purpose was to provide a reserve of aircrew to draw upon in the event of war. The Auxiliary Air Force, which had been formed in 1925 by the local Territorial Associations, was organised by squadron and used local recruitment similar to the Territorial Army Regiments.

Initially the RAFVR was composed of civilians recruited from neighbourhood reserve flying schools. The flying schools were run by civilian contractors who mainly employed instructors who were members of the Reserve of Air Force Officers (RAFO) who had completed a four-year service commission as pilots in the RAF. Navigation instructors were mainly former master mariners without any air experience. Recruits were confined to men of between 18 and 25 years who had been accepted for part-time training as pilots, observers or wireless operators. When a civilian volunteer was accepted for aircrew training they took an oath of allegiance (‘attestation’) and were then inducted into the RAFVR. Normally they returned to their civilian job for several months until they were called up for aircrew training. During this waiting period they could wear a silver RAFVR lapel badge to indicate their status.

The RAFVR during the Second World War

When the Second World War broke out in September 1939 the RAFVR comprised 6,646 pilots, 1,625 observers and 1,946 wireless operators. During the war, the Air Ministry used the RAFVR as the principal means of entry for aircrew to serve with the RAF. All those called up for Air Force Service with the RAF, both commissioned officers and other ranks, did so as members of the RAFVR under the National Service (Armed Forces) Act 1939.

By the end of 1941 more than half of Bomber Command aircrew were members of the RAFVR. Most of the pre-war pilot and observer Non-Commissioned Officers (NCO) aircrew had been Commissioned and the surviving regular officers and members of the RAFO filled the posts of flight and squadron commanders. Eventually of the “RAF” aircrew in the Command probably more than 95 percent were serving members of the RAFVR.

RAF Organisation

The RAF Second Tactical Air Force (2TAF) was one of three tactical air forces within the Royal Air Force (RAF) during and after the Second World War. It was made up of squadrons and personnel from the RAF, the air forces of the British Commonwealth and exiles from German-occupied Europe. Renamed as British Air Forces of Occupation in 1945, 2TAF was recreated in 1951 and became Royal Air Force Germany in 1959.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/academy/en/articles/art20130702112133719

RAF’s structure

The RAF is made up of one HQ (Air Command), Groups (Numbers 1, 2 and 22) – then stations, wings, squadrons and flights.

A RAF station is a permanent location. Many are aerodromes or airbases and home to one or more flying units called squadrons. Other stations are training or administrative centres.

The basic units of the service are wings, squadrons and flights:

Wings

Numbered flying wings have existed in the past, but more recently they have been created as and when necessary, according to operational demand. An expeditionary air wing (EAW) would be made up of aircraft, crew and support from several squadrons.

Just to confuse matters, wings are also the administrative units of an RAF station. A typical Royal Air Force flying station (not training) has administrative, engineering and operations wings.

Squadrons

The basic fighting unit of the RAF is the squadron. This is roughly the equivalent of an Army regiment.

The shape and composition of a squadron varies according to its role. Most flying squadrons are commanded by a wing commander who oversees around 200 personnel and between 12 and 16 aircraft.

Flights

A squadron is further divided into flights, under the command of a squadron leader. A squadron usually consists of three flights. Two will be fully operational and ready to go, while a third has responsibility for training newly arrived crews.

Air Command

At one time there was a separate bomber command, fighter command and strike command. Now there is just the one, Air Command, which is responsible for all RAF operations.

107 Squadron

From Wikipedia

No. 107 Squadron RAF was a Royal Flying Corps bomber unit formed during the First World War. It was reformed in the Royal Air Force during the Second World War and was operational during the Cold War on Thor Intermediate Range Ballistic Missiles.

http://www.historyofwar.org/air/units/RAF/107_wwII.html

At the start of the Second World War No.107 Squadron was a light bomber squadron, equipped with the Bristol Blenheim. It was one of the few bomber squadrons to begin active operations in 1939, taking part in the attack on Wilhelmshaven on the second day of the war.

The squadron was then involved in the fighting in Norway (April 1940), before taking part in the desperate attacks on German columns during the Battle of France. After the fall of France No. 107 Squadron took part in the attack on German invasion barges.

In March 1941 the squadron moved to Scotland and to Coastal Command and spent the next two months carrying out anti-submarine patrols and attacks on German shipping in the North Sea, before returning to Bomber Command and to Great Massingham in Norfolk.

In August 1941 the squadron’s Blenheim’s flew out to Malta, from where they attacked Axis targets in Italy, Sicily and North Africa. This lasted until 9 January 1942 when the surviving aircraft were withdrawn, and the detachment was dissolved.

In the same month the squadron began to receive Boston bombers back at Great Massingham, and in March operations from Britain resumed. For the next two years the squadron attacked German airfields and transport targets in occupied Europe.

The squadron’s final chance of duty came in February 1944 when it received the Mosquito FB.VI, and began to fly night intruder missions over Germany and occupied Europe. The squadron moved to Cambrai in November 1944, and remained there until the end of the war, still performing its night intruder duties. For three years after the war the squadron was part of the occupation force in Germany, before being renumbered as No. 11 Squadron in 1948.

No 305 Polish Bomber Squadron

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopaedia

The last of the Polish bomber squadrons under Royal Air Force command, 305 Squadron was formed at RAF Bramcote, Warwickshire on 29 August 1940. It was initially equipped with the somewhat obsolete Fairey Battle aircraft, but was reequipped in November 1940 with twin-engine Vickers Wellington heavy bombers. The unit began operational flying in April 1941. Its first mission was bombing of petrol and fuel storage tanks at Rotterdam in the night from 25 to 26 April 1941. Between June 1941 and August 1943 the Squadron was based at RAF Ingham.

In August 1943, the Squadron was moved to RAF Swanton Morley and thereafter ceased its affiliation with RAF Bomber Command; instead, it was absorbed into the freshly formed Second Tactical Air Force, a specialized arm of the RAF that was centered on tactical air strikes on vital enemy targets (such as bridges, supply trains, etc.) in the European Continent.

During this period, 305 Squadron was transferred to No. 2 Group RAF and converted briefly to North American Mitchell medium bombers before adopting the De Havilland Mosquito FB.VI, the aircraft that the Squadron operated for the remainder of the European campaign. Through 1944, the 305 was stationed at RAF Lasham in England and then briefly at RAF Hartford Bridge before moving to the Epinoy airfield in France in November 1944. During the Normandy Landings, the squadron destroyed 13,000,000 litres of the German fuel stored near Nancy, France. The squadron performed its last mission exactly four years after their first, in the night of 25 to 26 April 1945. After the hostilities ended, the Squadron continued to operate in Germany as part of the occupation forces and, after a brief return to England, was finally disbanded formally on 6 January 1947 at RAF Faldingworth, having already given up its aircraft on 25 November 1946.

http://www.polishsquadronsremembered.com/305/305_story.html

HISTORY OF No. 305 (POLISH) SQUADRON

Written by Wilhelm Ratuszynski

As the last of the Polish bomber units, No 305 (Ziemia Wielkopolska) Squadron was formed on 1 September 1940 at Bramcote. All flying personnel came from the 18 OUT located at the same airfield, many of them, members of the 3rd Air Regiment in Poland. In the beginning, the total personnel numbered 23 officers and 156 other ranks. The position of the first CO was given to W/Cdr J. Jankowski, who was assisted by his British advisor W/Cdr J. Drysdale. Operationally, the squadron was attached to the No. 6 Bomber Group.

Just as other forming Polish bomber squadrons, the 305 was equipped with single-engine Fairey Battles. And as the training progressed, the unit was reequipped with Vickers Wellington. This change came toward the end of November. Many new postings arrived as the number of crewmen and personnel had to be doubled. The airfield became too small, and the 305, together with its sister squadron No. 304, was moved to RAF Syerston. The move came on 2 December 1940.

Rather intense training now took place at a large, pre-war aerodrome. The crews were billeted quite comfortably, and theirs rosters crystallized into harmonized cells. This helped them to be much better prepared for upcoming operations over the enemy’s territory. These, on the other hand, came only at the end of April 1941.

Meantime, on 4 April, W/Cdr Kleczynski was given command of the squadron.

On the night of 24/25 April 1941, the squadron took part in operations for the first time. The fuel tanks of Rotterdam were bombed by the RAF, and among scores of British bombers over the target were three 305 Wellingtons piloted by W/Cdr Klenczynski, F/O Jonikas, and F/Sgt Trembaczynski. All three aircraft returned safely, and to commemorate this event, the day of April 25th, became the official Squadron Day.

On May 3rd and the second mission, the unit suffered its first loss. On its way to bomb Emden, the crew of F/O Nogal was shot down over Holland. A week later, the same fate met the crew of Sgt Dorman.

In May 1941, all four Polish bomber units sent crews every time Bomber Command prepared something for the Germans. The 305 crews bombed targets in Germany and France. The end of May was marked by excitement, as the news about German battleship Bismarck spread around, and the crews stood by with Wellington bombed up with armor-piercing bombs.

In June, the nights became much shorter, which resulted in part of the bombing runs flown in daylight. The good weather prolonged and German night fighters made many interceptions. Many RAF bomber crews were forced to ditch, and the 305 flown multiple of the air-sea rescue missions.

The A.O.C.-in-C. Bomber Command and the A.O.C. No. 1 Bomber Group inspected No. 304 and No. 305 Squadrons on 11th June, and H.R.H. the Duke of Kent visited them two days later.

On the night of 13/14 June, the 305 crews took part in a bombing raid against German battleships Gneisenau and Scharnhorst at Brest berths. Six 305 Wellington piloted by W/Cdr Klenczynski, S/Ldr Kielich, F/Lt Zach, Sgt Siemienski, Sgt Lewek, and Sgt Nalota, returned safely to Syerston. But the losses were inevitable. Just like all the other Bomber Command units, the 305 had its share of fatalities. The most painful for the squadron was the loss of S/Ldr Kielich, whose aircraft was damaged by flak over Boulogne and the crew bailed out over the channel. Read F/O Idzikowski’s relation.

It is safe to say that, just like other Polish squadrons, the 305 loaded with exceptionally good human material, and its service with the Bomber Command was not unnoticed. Quite telling is a report of the RAF Swiderby CO’s, G/Cpt Pendred (who by that time familiarized himself with Poles and their novel customs) to the HQ of No. 1 Group, and which mentioned the F/Lt Korbut No. 305 Squadron navigator:

“I forward report in respect of F/O S. Palka, who has just returned from the Specialist Navigation Course held in Canada. I understand that there were 16 officers on this course, two of them Poles. On passing out, one of the Poles was top (F/Lt C. Korbut from No. 305 Squadron), and the other, F/O Palka, was third. You will note that the latter’s report is excellent and provides us with yet another proof if one is wanted, that the Poles are not only enthusiastic fighters but also earnest learners, with brains and capabilities equal if not superior to our own.”

The summer months of 1941 weren’t easy for the unit. The personnel had to get used to strenuous work and… losses. In July the 305 made 48 sorties bombing targets in L’Orient, Brest, Frankfurt-on-Main, Emden, and Dunkirk, and twice on Bremen, Cologne, and Rotterdam. Several aircraft were lost. Fortunately, the PAF reserves at Blackpool Depot were not yet depleted and the replacements were posted promptly. So, just like in any other squadron, the training never stopped.

Meantime, on 20 July 1941, the unit moved to RAF Lindholme, the “Polish” station in York, commanded by W/Cdr Makowski, former Co of No. 300 Squadron. The unit was partially converted to Wellington Mk. II, and then to Mk. IV. The latter powered by air-cooled American Pratt and Whitney Twin Wasp engines.

W/Cdr Kleczynski gave up his command of No. 305 Squadron on August 8th. He was found not longer fitted for the task, having been wounded many times, still suffering from injuries sustained in the Polish campaign in September 1939. W/Cdr Robert Beill replaced him.

On 27 September, the Wellington W5557 returning from operations over Cologne was forced to land. The aircraft fell on a farm near Hatfield Moor, killing four crew members and three civilians.

The end of 1941 was marked by the loss of several crews, the last one on 23 December when the returning from Cologne, Wellington piloted by F/O Golacki, crash-landed in Leicester without survivors.

In 1941 the squadron totalled 284 missions flown in a time of 1480 hours, and it lost 66 airmen killed.

1942, was the year when the Polish Bomber Force hit the enemy very hard, but in return was stuck itself with biggest losses. This resulted from an increase in its operational effort. The 305 was very important part of it.

On the anniversary of the first operational flight, and 24 April 1942, the Polish C-in-C General Sikorski visited the Syerston, and stationing there No. 304 and 305 Squadrons. The celebrations were preceded by a record number of crews taking part in a raid on Rostock. All returned safely and after releasing their entire load on target.

As usual, missions to be flown gained in strength and frequency with the coming of the spring. The first big one was a 1,000-plane raid on Cologne on the night of 30/31 May 1942. Several crews from the 305 took part in it. That month, the unit has begun to fly a new type of mission: mining entries to the German ports. These were difficult and dangerous flights, but the war itself was a dangerous business.

Losses kept coming – usually one or two a month crews lost – as the year progressed. Some of them were more painful.

On 1 June lost was the Wellington piloted by S/Ldr Hirszbandt, OBE. In a citation to his decoration, we read: “F/Lt Hirszbandt has completed 19 sorties over enemy territory involving over 99 flying hours. As a captain of the aircraft, he is outstanding. His determination to reach his objective shows a fine offensive spirit and in his complete disregard of enemy opposition, he displays the courage of the highest order. This offensive spirit, skilful pilotage, and outstanding leadership have set the finest example to all, and have contributed in a large degree to the successes of his Squadron.

“On one occasion, when detailed to attack Hamburg, the aircraft he was piloting was caught and held by searchlight, and heavily engaged by enemy flak. He determined notwithstanding to press home his attack as he was carrying a single bomb of 4,000 lbs. and he, therefore, came down to 8,000 ft. to bomb the target and a direct hit was claimed.

“After the attack, by skilful pilotage, he succeeded in escaping from the searchlights and flak and set course for base. When over the sea in the region of Heligoland, his aircraft was attacked by an enemy fighter, which damaged his aircraft and wounded his rear gunner. As the result of the encounter, which was shaken off by his skilful evasive tactics, his air-speed indicator was unserviceable, one propeller was damaged, his fuel and oil gauges ceased to function and the tail unit, rear turret, fuselage, and main planes were also damaged. His outstanding airmanship alone enabled the aircraft to be brought back to base, and though his aircraft was damaged in the landing, he undoubtedly by his efforts saved the lives of his crew and much valuable equipment.”

On 26 June the 305 Wellington with the W/Cdr Skarzynski on board, the CO of the RAF Lindholm, had to ditch in the North Sea after suffering flak damage. Except for Stanislaw Skarzynski, who became famous for his solo flight over the Atlantic in 1933, a British Navy ship rescued the whole crew.

During the second half of 1942, the squadron continued with maximum effort; the crews and aircraft were slowly depleting and it became harder and harder to send out the same number on missions. The unavoidable losses occurred periodically, but comparing to the previous year, there were many more safe returns in the unit. To replace looses they had to scrape the bottom of the barrel at the Polish Depot in Blackpool.

At the end of this backbreaking year, No 305 Squadron totaled 587 operational flights in 3,273 flying hours, thus more than double of its previous year effort. The unit sustained about the same number of losses, both in aircraft and flying personnel.

The beginning of 1943 saw a lot of new faces in the unit. Several crews from the reorganized No. 301 Polish Squadron were transferred to Hemswell. On January 18, the unit had a new CO, W/Cdr Tadeusz Czolowski.

Soon the so-called “Battle for the Ruhr” commenced, and the RAF’s Bomber Command stepped up its effort to cripple German heavy industry. With that came improved equipment and techniques for its use. In April, the 305 was converted to Wellingtons Mk. X, equipped with two Bristol Hercules 1,675 hp engines. These were much better aircraft to fly and the pilots welcomed the change very much.

In this new offensive, the squadron participated till the end of July, when it was decided to move the unit to the newly created 2nd Tactical Air Force. This was followed by a conversion to light bombers and a reduction of the crews. Meantime, on 22 June the squadron relocated to RAF Ingham only a few miles away from Hemswell. The conditions were quite different at the new place, where the crews were billeted in Nissen huts and the whole personnel was scattered all over the local spots. The airfield itself was a rather pitiful picture but had one big advantage: long, flat, and easy approaches. On 28 July, W/Cdr Kazimierz Konopasek assumed command of the unit.

When the 305 left the Bomber Command its record wasn’t outstanding, but it shows business terms it should be described as a “very solid performance”. From its first operational sortie on 25th April 1941 to the last one on 3rd August 1943, the squadron flew 1,117 sorties and accounted for 1,555 tons of bombs dropped and mines laid. It lost 136 killed, 10 missing and 33 taken prisoner – a total of 179 casualties, equivalent to more than a full operational crew each month for two and a half years. During that time the unit lost 46 planes.

Without aircraft, the unit moved to Swanton Morley (Norfolk), where it soon received North American B-25 “Mitchell”. After a month of conversion to the new aircraft, the unit returned to operational flying. This time its targets were flying-bomb launching-sites, enemy headquarters, and fortifications in the Cape Gris Nez region. The one biggest change for the squadrons was a fact that the missions were now flown in the daytime and with fighter cover. But very few Polish crews flown more the 10 missions on Mitchells, as the word was spread that the unit soon will reequip once again to De Havilland’s wonder: “Mosquito”. During the brief period of flying the American bomber, the 305 suffered only one loss, when on 14 November the aircraft piloted by F/Sgt Anglik crashed during a training flight.

On 19 November the squadron moved to a better airfield at Lasham in Hampshire. Soon after that, the first Mosquitoes were flown in. The change from Wellingtons to Mosquitoes brought inevitable personnel shifting. Needed were pilots of a more aggressive, fighter-style of flying, and those who did not have enough skills and were considered “truck drivers” had to leave. But those who stayed were much gratified. The Mosquito was the very best what the RAF could employ. Because there wasn’t enough of Polish pilots and navigators ready for conversion, the squadron received eleven British complete crews, which formed separate Flight commanded by a British officer. Poles formed nineteen complete two-person crews.

Until the D-Day (6 June 1944) the unit carried out its main duty: Ranger and Intruder operations. By day they chiefly attacked V-1 sites, and by night enemy’s night fighter airfields in France, Belgium, Holland, and Germany in support of Bomber Command operations. Although the squadron never sent many aircraft for one mission, it was rather busily engaged in those operations.

With the start of the Invasion, the 305 stepped up its operations significantly. Just as almost all RAF units engaged, the squadron had to deliver a maximum effort that day. Several crews made more than one sortie. In support of the operation, Polish Mosquitoes targeted railway stations, tracks, bridges and trains, reserve groupings, and forces on their way to the front. Between D-minus-one Day and the end of August 1944, the 305 made over 500 sorties on special missions and in support of the invasion.

As the Allies progressed on the continent, the 305 operations slowly shifted back to the role of harassing Germans elsewhere. On 16 June, lost were S/Ldr Herrick, British Flight “B” commander with the navigator F/O Turski. A German fighter shot down their plane during a Ranger operation in Denmark.

On 11 July the squadron lost two planes in operations, both to the enemy’s flak in France. Only S/Ldr Lagowski, a navigator, managed to survive and evaded capture. After a few weeks, he returned to the unit. On the last day of the month, the W/Cdr Konopasek was rested and W/Cdr Boleslaw Orlinski DFC took over the CO post. He was an almost legendary figure in Polish aviation and one of the unit’s many pilots of advanced age. Orlinski became famous for his record-breaking flight from Warsaw to Tokyo in 1926. Most of the others were well over thirty and with thousands of flying hours. No wonder that the nickname “Flying Blimps” stuck with airmen of the 305. It probably originated from the prewar cartoon character: Colonel Blimp.

Occasionally, the atmosphere of excitement swept the unit, as some special missions were introduced. On 2 August 1944 at dusk, nine Polish Mosquitoes led by S/Ldr Rayski, successfully attacked German Sabotage School at Château Maulny. In another “special commission” sortie, six planes led by W/Cdr Orlinski, destroyed big German fuel depot at Nomexey in France. Although both targets were heavily defended, the squadron suffered no losses.

Worth mentioning is many sorties flown in support of Allied ground troops trying to root out Germans from the island of Walcheren and Zeeland. These German positions prevented the use of the port of already liberated Antwerp. During September, October, and early November, the 305 bombed these German positions by night, lighting them with special flares first.

Unfortunately, around that time, the unit lost several crews, both in operations as well as in training. On 24 September, two Mosquitoes collided in mid-air. One of the crews was British; in another, Chaplain Samulski flew as a navigator. There were no survivors. In November five planes were lost and four crews, two Polish and two British. F/Sgt Haas and P/O Wilczewski managed to reach Allies lines on a badly damaged plane and safely bailed out.

On 19 November, the unit was moved to the continent, and to occupy part of the A-75 airfield at Epinoy, near Cambrai. There, just like all the other RAF units, the squadron operated in very demanding conditions. After fighting mud for over a month, the personnel had to clear the heavy falls of snow in December, nearly daily during the German offensive in Ardennes. All hands on deck were called when on Christmas Eve the squadron took off twice to hamper advancing Von Rundstedt’s army.

The squadron welcomed New Year in a somber mood. On 1 January 1945, the Luftwaffe in a last desperate attack tried to deliver a blow to Allies air forces stationed on the continent raiding their airfields on the early morning hours. The list of targets in the operation “Bodenplatte” included Epinoy. The airfield received several bombs, but the squadron suffered no losses, both in equipment and personnel.

In January five Polish crews completed their operational tours and left the unit. This caused a curious situation when in the Polish squadron majority of the crews were British. Among the non-Polish crews, the one would find a rather surprising number of other nationalities. There was an Estonian, a Norwegian, a Hindu (who got the Polish Cross of Valour), two Canadian crews, Welshmen, Scots, and Englishmen. There were also a few guys from the West Indies.

At the end of February, the 305 took part in the biggest aerial operation (“Clarion”) of the war, when 7,000 allied aircraft attacked defending Germany. The unit sent out sixteen Mosquitoes, which for half an hour strafed targets of opportunity in the area of Bremen-Hamburg-Cologne. The squadron created havoc on the ground but 10 of its planes returned damaged, three on one engine. One British crew was shot down.

From F/Lt Referowski’s DFC, after-mission report we learn that it was an eventful mission. On reaching the target area, together with his No. 2, he patrolled the sector allotted to him, looking for movements, of which none were observed. He then made a very successful bombing attack on a factory three miles NNW of Basbeck, scoring a direct hit on a large factory building. Continuing his patrol he strafed a wireless station three miles east of Basbeck, attacking it three times despite intense and accurate machine-gun opposition, and scoring numerous hits on buildings. He then followed with a successful attack on two barges and a vessel on the river Oste, and strafed an engine with five coaches on the railway line between Basbeck and Stal, receiving intense and accurate light flak, which damaged his fuel tank what resulted in fuel leakage. On his return journey, in the Zuider Zee area, he saw a Mosquito aircraft flying on one engine, and, despite fuel shortage, (which eventually forced him to land short of his base) he turned back to its assistance.

On 1 March the squadron consisted of 25 crews, eleven of them Polish. That month the unit recorded 212 operational flights without losses.

In April 1945 the 305 saw less flying but lost two British crews during Intruder operations. The last operational sorties were flown on the night of 25/26th when six planes operated in the area of Westerland and Flensburg.

During its service with the 2nd TAF, No. 305 Polish Squadron totaled 2310 nighttime and 158 daytime operational flights; dropped 1213 tons of bombs, and spent 360 100 cannon shells. It lost 25 Polish and 19 British airmen. It also lost 35 planes.

© Polish Squadrons Remembered

21 bomber squadron

http://www.historyofwar.org/air/units/RAF/21_wwII.html

At the start of the Second World War No.21 Squadron was a light bomber squadron, equipped with newly arrived Blenheim IVs. Like many bomber squadrons it had a quiet start to the war, but that ended in May 1940 with the German invasion of the Low Countries. No.21 Squadron took part in the costly attacks on the advancing Germany columns, before at the end of May moving to Lossiemouth, to join Coastal Command.

The squadron spent most of the next two years operating as an anti-shipping unit, alternating between Lossiemouth and Watton between June and December 1941, before moving to Malta at the end of December 1941 to attack the vital Axis supply convoys attempting to get supplies to Rommel in North Africa.

The squadron was disbanded on Malta on 14 March 1942, and immediately reformed at Bodney, this time as a day bomber squadron. The new squadron inherited No.82 Squadron’s Blenheims, which were soon replaced by the Lockheed Ventura, but it was not until the arrival of the Mosquito FB Mk.VI in September 1943 that the squadron gained a truly effective bomber. Its first operation as a day bomber squadron was an attack on the Philips works at Eindhoven on 6 December 1942.

The Mosquitoes were used for a mix of pinpoint daylight raids and night raids until February 1945, when the squadron moved to France. From then until the end of the war the squadron flew night intruder missions over Germany, helping add to the “mosquito panic”. After the war the squadron spent two years as part of the occupation forces in Germany, before being disbanded in November 1947.

The Squadron moved to bases in France in February 1945, and then to RAF Gutersloh in Germany in December 1945. It provided courier services between Blackbushe and Nuremberg in support of the Nuremberg Trials before it was disbanded on 7 November 1947.[2][28]

Aircraft

August 1938-September 1939: Bristol Blenheim I

September 1939-July 1942: Bristol Blenheim IV

May 1942-September 1943: Lockheed Ventura I and Ventura II

September 1943-October 1947: de Havilland Mosquito FB Mk.VI

Location

2 March 1939-24 June 1940: Watton

24 June-29 October 1940: Lossiemouth

29 October 1940-27 May 1941: Watton and Bodney

27 May-14 June 1941: Lossiemouth

14 June-17 July 1941: Watton

17-25 July 1941: Manston

25 July-7 September 1941: Watton

7-21 September 1941: Lossiemouth

21 September-26 December: Watton

26 December 1941-14 March 1942: Luqa

15 March-30 October 1942: Bodney

30 October 1942-21 March 1943: Exeter

21-24 March 1943: Methwold

24 March-1 April 1943: Oulton

27 September-31 December 1943: Sculthorpe

31 December 1943-17 April 1944: Hunsdon

17 April-18 June 1944: Gravesend

18 June 1944-6 February 1945: Thorney Island

6 February-17 April 1945: B.87 Rosières-en-Santerre

17 April-3 November 1945: B.58 Melsbroek

Squadron Codes: UP, YH

Duty

1939-June 1940: Light Bomber squadron

June 1940-March 1942: Coastal Command anti-shipping

March 1942-1945: Light Bomber squadron, ending with 140 Wing, 2 Group, 2nd TAF